Serban Savu (a conversation)

We sat down with Serban Savu, the painter who represented Romania at the Venice Biennale with a huge social polyptych.

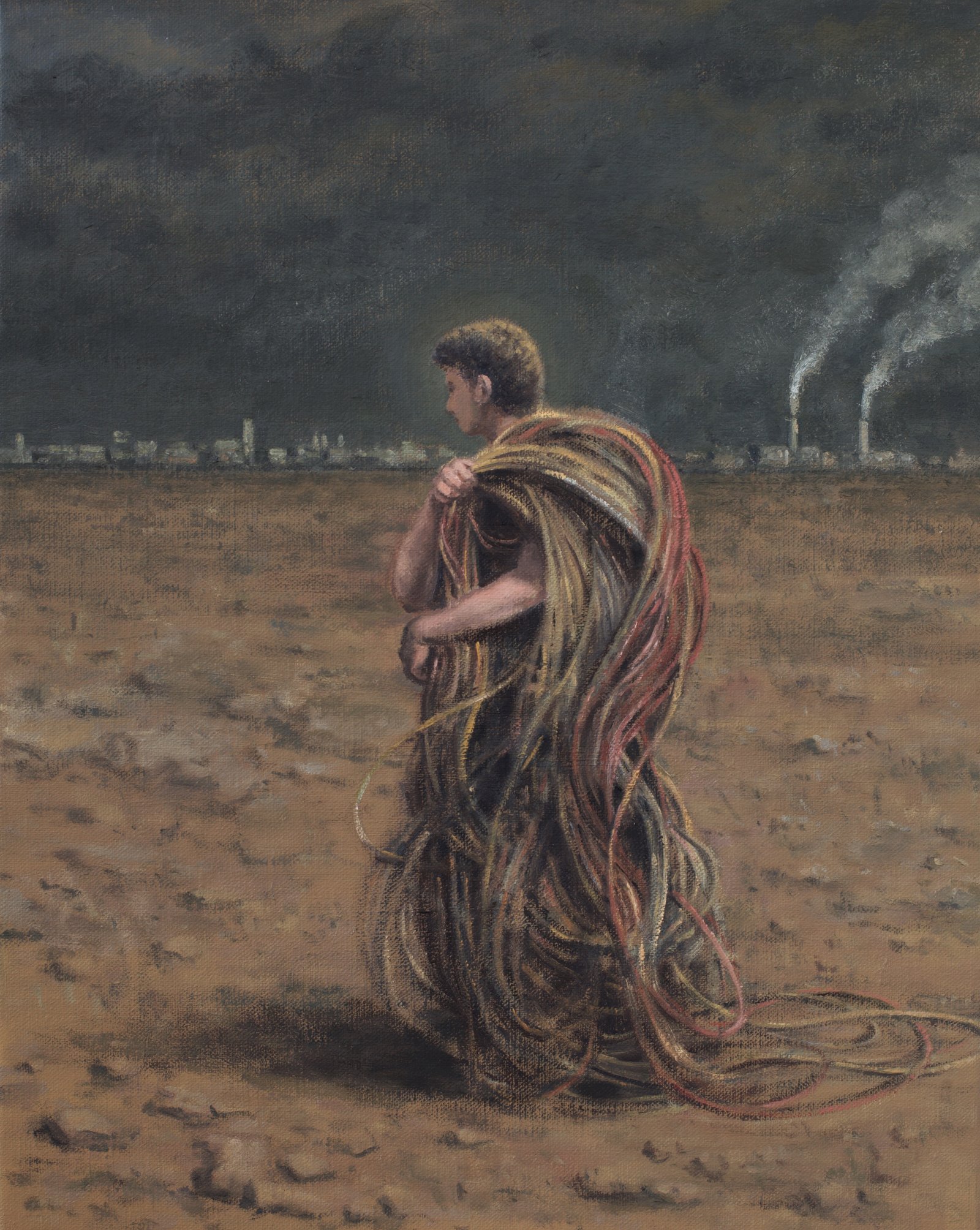

In Șerban Savu’s paintings, common people are going about their daily lives. Having been studied with the patience of a voyeur over consecutive days as they inhabit the neighbourhood, people who don’t necessarily know each other eventually find themselves on the canvas, within the same perimeter. In most paintings, an aerial gaze plunges into an urban-rural landscape. It is here, at the city’s periphery, that several decades of history are distilled. Other series place the characters on sites reminiscent of archaeological ruins or depict interiors where artworks from different times surface in loose renditions, juxtaposing multiple registers and realities. These operate as dynamic lieux de mémoire, engaged in a continuous work of recovering and restoring.

Long present in Șerban Savu’s paintings is the relationship between work and free time. His attention to the figure of the worker—a protagonist for the glorification of labour in the official art of communism—came as a persistent attempt to understand the realities of the Romanian society after the collapse of a utopian project. Savu revisits the theme in the exhibition What Work Is created for the Romanian Pavilion at the Biennale Arte 2024 in Venice*. As the exhibition statement synoptically reads, “[it] invites an exploration into the iconography of work and leisure, drawing inspiration from historical realism and the propaganda art of the Eastern Bloc. Instead of dismantling these discourses, Savu challenges them by rearranging their tropes.” Destabilizing the dichotomy, the focus of the exhibition falls on the undecidable: moments of ambiguity in which people are inactive at work in a state of lethargic indifference and of disengagement from the productive system.

In the main hall of the Romanian Pavilion, over 40 paintings—a cross-section of Savu’s work over the last fifteen years—have been encased in a vast polyptych, creating an astounding fresco-like effect. Across the wall of paintings, one of four architectural models on display integrates a scene of relaxation. Titled True Nature and made in mosaic, it was coined as a “historical revenge” of those who exerted themselves in the past and are now taking their time to rest. The work miniaturised a monumental mosaic imagined by Șerban in antithetical dialogue with Aurel David’s The Plowman of the Universe, a socialist-realist artwork from the 1970s that still adorns the I. A. Garagin Youth Centre in Chișinău, in the Republic of Moldova.

Complementing the presentation in the Romanian Pavilion, the New Gallery of the Romanian Institute for Humanistic Culture and Research in Venice has been transformed into a mosaic workshop. Artists from the Moldavian city of Chișinău and from the Romanian cities of Iași and Cluj have been invited to recreate the picnic scene from True Nature into a large-scale mosaic. The work being made at the workshop throughout the biennale as a continuous performance open to the public is to be donated upon completion and placed on a building in Chișinău, closing the circle of inspiration, creation and production.

Georgiana Buț – The exhibition you created for the Romanian Pavilion draws links between the type of presentation, a contemporary reconceptualization of the polyptych, and the historical art of Venice, the city where the exhibition is located. I imagine it was a natural gesture for you, due to your tight relationship with art history and having spent two years in the lagoon. You often mention how you became enthralled by the Venetian painters, discovering works such as the Polyptych of San Vincenzo Ferrer by Giovanni Bellini in situ. Moreover, the polyptych as a form is not new in your art, any more than the concept of a being in-between work and leisure. It’s very interesting that you chose a form proliferated by religious art to depict lay scenes and highly topical issues. What motivated you to bring them together?

Șerban Savu – The first polyptych I made was the “Polyptych of Work and Leisure,” back in 2014, and for this year’s exhibition in Venice, I revisited the idea from ten years ago on a completely different scale and in a different format, adapted to fit the Romanian Pavilion from Giardini. Art history, whether we are talking about recent or older art, has always interested me and I like to use the language of art from all times to discuss current ideas. In this case, I superimposed the polyptych as a form of religious art with ordinary scenes of work and leisure, borrowing the main themes of Socialist Realism, but stripping them of any ideology, of propaganda. Basically, it reflects what happened in the Romanian society after the fall of the Communist regime, when political ideology was replaced by religion.

Georgiana Buț – Encased in the large panel, there are over 40 paintings on display, selected from a considerable time interval (about 15 years). This installation is of great complexity in the way it welds the theme of the exhibition and its form. The composition responds to the scale of the architecture and offers an immediate, comprehensive glance, achieving the overall effect of a fresco. During the opening days of the biennale, I had the chance to notice this effect on the viewers, their reactions of astonishment as they entered the main hall of the exhibition. Furthermore, the composition allows for multiple pathways that unfold in time, with a certain rhythmicity, as one walks through space. How did you think about the experience of the viewer in the process of composing the polyptych?

Șerban Savu – First of all, I wanted the polyptych to be monumental, to give the viewer the feeling of being in front of a social fresco. Then, I wanted this installation to suggest the idea of a religious polyptych, that’s why I embedded the works in the wall and grouped them on three levels. Of course, we didn’t follow the traditional arrangement of a polyptych in all its respects, for example we introduced the predella containing the small works in the middle part, not in the bottom part as we usually find it, so it can be easier for the viewers to see it. One can also observe a compositional delimitation reminiscent of a classic polyptych: the central part is composed differently and is higher than the lateral parts.

Last but not least, we paid great attention to the light because we wanted to primarily use natural light, the most appropriate for painting and so, we covered the skylights with a dispersion film to get rid of any shadow that might interfere with the reading of the work.

Georgiana Buț – How did you perceive the architecture of the Pavilion designed by Brenno del Giudice? It’s a structure that deposits layers and layers of history and ideology.

Șerban Savu – I have seen the architecture of the pavilion more than 20 years ago, in 2003 when I visited the Venice Biennale for the first time and afterwards, I returned to see every edition of the Biennale so far. I was also aware of its history, built, as you mentioned, by the Venetian architect Brenno del Giudice, during Mussolini’s fascist regime. However, for the exhibition in Venice, I focused on my usual artistic practice rather than making a site-specific installation. Of course, there is a dialogue between two of my architectural models presented in the exhibition and the building of the pavilion: the socialist block (True Nature, 2021) and the Brush Factory (Lunch Break, 2024), two emblematic buildings built in the ’70s by the Romanian totalitarian regime.

Georgiana Buț – Opposite the wall of paintings, there are these 4 “in volume” works at the intersection of architectural model and sculpture, each incrusted with a small mosaic scene. One of these is an archaeological site, Untitled (The last provincial unearthings), 2023. Could you tell us more about your fascination with archaeology? Is there a connection between this growing interest and working in mediums other than painting?

Șerban Savu – My interest in archeology is not new and it is closely connected to the trips I make around the Mediterranean and the fact that from a young age I was familiar with the myths of Ancient Greece. I have seen a lot of archaeological sites and ancient art museums in the last 20 years but only in the last 5-6 years archeology has become a theme in my painting and recently, also in the new mediums you mentioned. I don’t think there is a connection between my interest in archeology and an attempt to work in other mediums. I resorted to other mediums because in time I came to some ideas that could not be expressed in painting, so I ended up making mosaics or architectural models/objects.

Georgiana Buț – You depict the reality of common people drifting, readjusting amidst societal shifts. Talking about some of the themes you deal with in your painting you made an observation that intrigued me: “I am interested in the inconsistencies that stem from the way society is constructed and from its past historical experiences. These are things that have been on my mind for a very long time, I just didn’t know I could paint them.” [emphasis added] What did you mean, precisely? The fact that these subjects can be dealt with in pictorial language? Your ability to portray them convincingly? How did this discovery come about?

Șerban Savu – After staying for two years in Venice, between 2002 and 2004, on a scholarship, I returned to Cluj and realized that the experiences and the life lived in another culture helped me to see more acutely the realities around me. This new perspective made me understand that the things I was thinking about and which I was observing in the immediate reality could become the subjects of painting or better said, I could understand them better through painting. I would say that it was a kind of an intuition-revelation through which I found a way to express those ideas in pictorial language.

Georgiana Buț – You are concerned with the function of painting and the role of the painter at different moments in the history of art. When you rendered in your paintings some scenes of monumental works from the 1970s—Aurel David’s The Plowman of the Universe from the I. A. Garagin Youth Centre in Chișinău, or the mosaic on the facade of the Steagul Roșu factory in Brașov—you reflect on the experience of the painter in the socialist period, as you say, in order to find out “from the inside” their percentage of authenticity in the midst of propaganda. Other times, you remake classic paintings in your work, a process of “getting into their guts.” How do you experience being a painter today? And how would you describe your own relationship with work?

Șerban Savu – Indeed, by taking up some socialist realist public works and integrating them into my paintings, I tried to better understand the constraints or freedoms of the artists from a troubled era. For me, the relationship with the past is always a negotiation and a way to define and reposition myself in the present. I have the feeling that I don’t understand who I am if I don’t first look at the past, be it recent or distant. For an artist who uses this “old” medium of artistic expression—painting—, looking towards the past is even more necessary and inspiring but not out of passéism or nostalgia, on the contrary. The past contains all the imagination of humanity and at the same time, all the seeds of the future.

As an artist, I am interested in the present and in the time which I live in and which I want to talk about, but I cannot do it without looking back.

In other words, and to answer your question more precisely, routine is for me the only way in which I can work, in which I can outline and deepen my ideas, in which I can build images. On the other hand, inspiration for me means getting out of the routine and here, unfortunately, I haven’t found any recipes so far.

Georgiana Buț – Through your works, and in your discourse on them, you are constantly raising questions about the nature and purpose of painting. Some of the issues that we touched upon in this conversation could be viewed as pertaining to philosophy of art. Is aesthetics important for you, do you find it relevant for your painting in particular? And I dare broaden the questions: do you think that philosophy of art—and not just the history of art, so active in your works—can tell us something about painting today?

Șerban Savu – Art and the philosophy of art have been inseparable since the time of the Ancient Greeks and I don’t see how things could change in the future, in the societal model we live in.

I think that for every artist the question “why I make art” remains a very important question that deserves to be periodically reinspected. For a painter like me, the more specific questions “why I paint” and “why I don’t choose another medium to make art” constantly appear and sometimes I try to find answers also through painting.

As a viewer, I have the same questions about the nature and meaning of painting, otherwise it would remain only a superficial sensory experience.

Georgiana Buț – You often draw parallels between the pictorial and the literary processes. Your monograph from 2019, Drifting (Idea Design & Print, Cluj-Napoca, 2019), was structured around poems by Philip Levine. Moreover, the exhibition at the Romanian Pavilion is titled after one of his poems, What Work Is, highlighting threads of continuity in your practice over the years. Even in describing the dialogue with the works of Nana Esi and Sophie Keij, the Brussels-based duo you invited to respond to the project in Venice, you make use of a literary metaphor, likening Atelier Brenda’s intervention to a cover that envelops a book. Could you tell us more about the role that literature plays for you? Is there a book that has particularly captivated you in terms of construction, of working technique?

Șerban Savu – My connection with literature is very direct: my father was a writer and the relationship with literature was mediated in the family from the beginning. I never tried to write literature or anything else on my own initiative and writing is something very difficult for me, maybe because my father had a very dominant personality. But I remained a reader, not very zealous, but I always have a literature book with me and not infrequently I find inspiration or at least a creative mood when I read.

Probably the most impressive books—and so different from everything I’ve read so far—are The Iliad and The Odyssey. At the moment, a novel by Richard Flanagan, The Narrow Road to the Deep North, is waiting for me on my nightstand but only after I finish Aldous Huxley’s Island.

*Note: For the 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia 2024 (20 April – 24 November 2024) the Romanian Pavilion presents a project by Șerban Savu and Atelier Brenda, curated by Ciprian Mureșan. Titled WHAT WORK IS, the project unfolds in two venues: Giardini Biennale and The New Gallery of the Romanian Institute for Culture and Humanistic Research in the heart of the Cannaregio district. Invited to respond to Șerban Savu’s project, the Brussels-based graphic design studio Atelier Brenda (Sophie Keij and Nana Esi) offers a site-specific intervention on the façade and in the lobby of the Romanian Pavilion. A project initiated and supported by IDEA Foundation.

September 25, 2024