Benedetto Antelami: praise of gravity

Benedetto Antelami carves the most spiritual and quotidian figures in the heaviest Medieval stone, founding blocks of cathedrals and cults.

The figure of Benedetto Antelami resonates in the words of Rodolfo il Glabro, a monk and chronicler of the 11th century, who unlike many others didn’t believe the world would end in the year 1000. On the contrary, he praised a great rebirth of Christendom and a new desire to open construction sites, proclaiming that “a white mantle of churches, a crusade of cathedrals” will be spreading over European Christianity. Architecture and sculpture are the real arts in the heart of the Middle Ages, from the cathedrals of Chartres and Notre-Dame to Le Mans and Bourges, from Modena, Ferrara, Piacenza to Fidenza, Pisa, Cremona, Parma and Como: the sense of the divine was given by the heaviest material that is marble. [Here is our study dedicated to medieval architecture in the region of Como. Ed.]

It is curious that the most spiritual art was carved in earthly stone, marked by both divine and demonic forces. The Middle Ages are a composition of opposites. The sculptor Benedetto Antelami (1150 ca – 1230 ca) leads us face to face with this antinomy. The route starts from the Parma baptistery, with twelve altorilievos representing the Months and two sculptures of the Seasons, now temporarily lowered to the floor, moved from the first internal gallery located seven and a half meters high. A few questions arise. What were such profane sculptures doing in a Baptistery, a temple of God and spirituality? What was the place of a farmer harvesting turnips, which represents the month of November, or the curly figure with the spade of the month of February in church? Why were these sculptures accompanied by the signs of the zodiac? The Aquarium tile even depicts a medieval kitchen where salami and sausages are prepared. They might as well be the ancestors of those culatello and strolghino for which Parma is famous.

We are faced with a direct and unambiguous representation of reality, which seems to contrast with the religious environment in which the works are placed. This contrast did not exist at the time though. People simply believed that life had a double side. “All flesh will see the salvation of God,” says Luke in the Gospel. Simple people who entered the baptistery or the cathedral first “read” the sculptures that unfolded on the three portals of the facade: the biblical stories of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, of Barlaam and Salomé. With its allurements, the outside world was a place of threat, of lies. Inside however were the Christ and the Baptist, ready to redeem sins with their sacrifice. The sculptures constituted a long chain of salient highlights, a path. After crossing the Portal of Life into the baptistery, there stood the sculptures of the Months, in which one could find the representation of work as moral edification. In Antelami there is no longer the biblical condemnation that God had destined for Adam, “you will eat your bread by the sweat of your brow.” Work was instead useful and redeemed humans through a dream of renewed earthly paradise.

The year in Parma began with spring, as it did in ancient Rome. This inaugural season is depicted by Antelami as a charming girl with a refined classic tunic and a royal crown of primroses. “In the Middle Ages there was a great difference between the frontal figures that send a symbolic message and those portrayed in profile, who live within their space and tell their story,” explains the medievalist Chiara Frugoni. Spring and Winter look the viewer in the eye, expressing the incarnation of Christ that took place in Spring with the announcement of the archangel to Mary, and alluding to his death and rebirth. Winter is represented by a great old man with a beard in extravagant clothing, half naked and half dressed. January is the two-faced Janus of Rome.

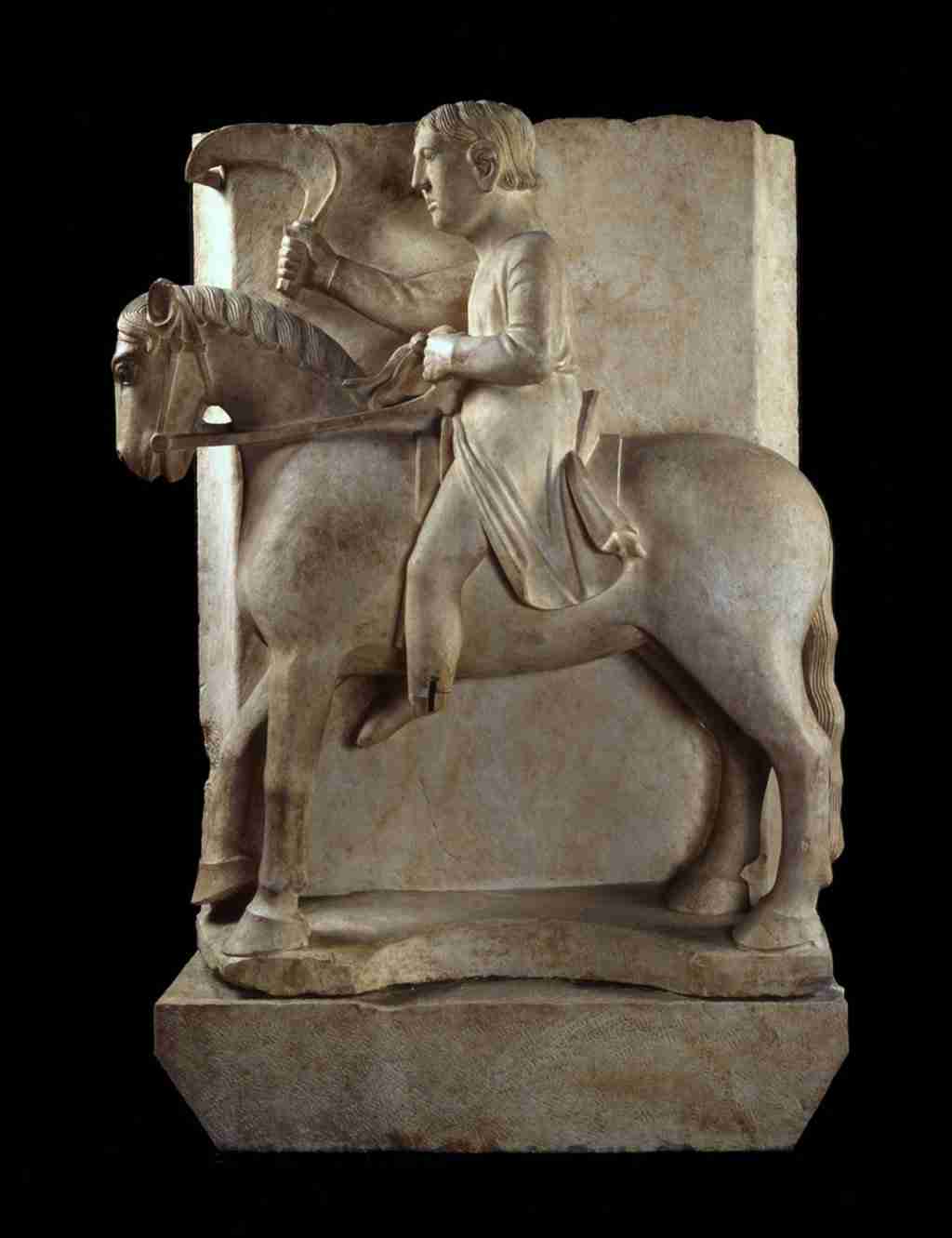

In the altorilievos of March, April and May, the iconography represents noble figures, young people with hedgehogs, a novel expression by Antelami that took inspiration from the statues of Roman antiquity. The knight of the month of May, with the sickle in his hand certainly did not do agricultural work, but he had the right to cut the oats of his master. The other months show peasants who work in the countryside. The perspective construction of July is daring, with the tall ears of wheat that act as a pedestal for the horses. A capped farmer cuts bunches in the representation of September, and in October the same figure wears shoes and has a long beard, symbolizing the ageing of the year.

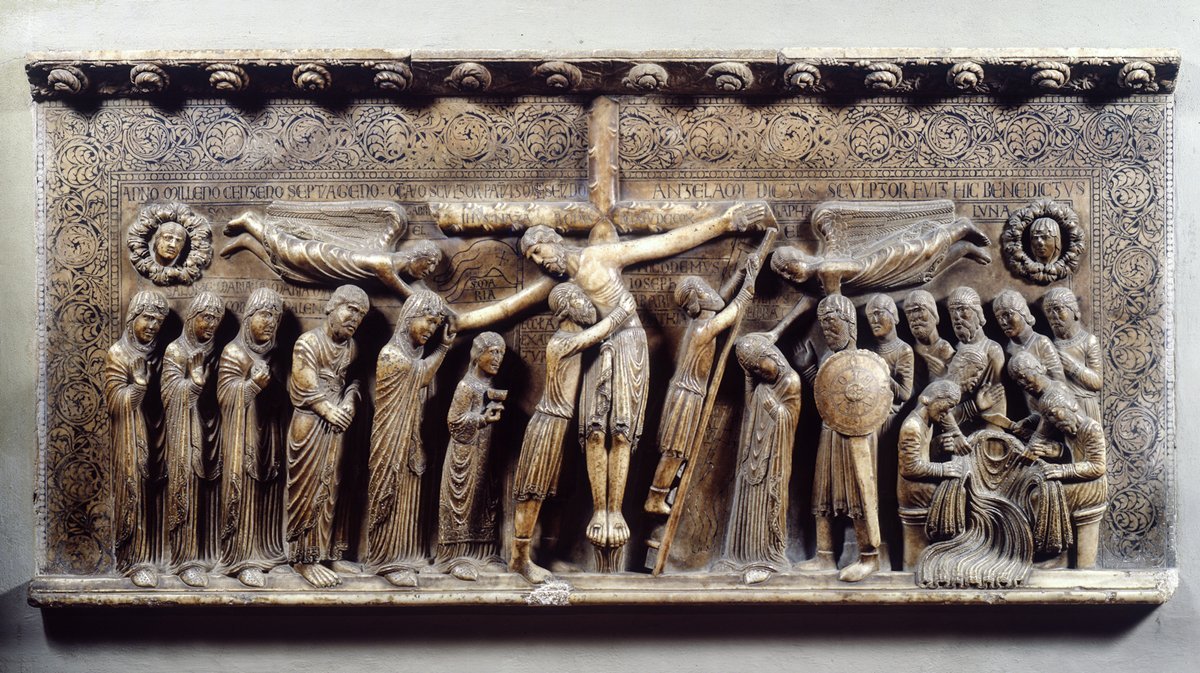

We could close the tale of Benedetto Antelami here, and call it a beautiful medieval story. Though a question keeps coming back: did this artist really exist? There are two autographs that confirm his presence. The first is on the North portal of the baptistery and says: “In 1196 the sculptor called Benedetto began this work.” The second is on the slab of an iconographically revolutionary Deposition, walled up in the Cathedral of Parma. It says: “In 1178, in the second month, the sculptor completed (the work), this sculptor was Benedetto known as Antelami.” Even where his work is signed and dated, there exist difficulties of interpretation.

Is Antelami only the sculptor or also the architect of the entire Baptistery? The addition of Antelami to the name Benedetto was used for families of builders from the Val d ‘Intelvi, who worked in Genoa. Yet there is no evidence that Benedetto came from that region. If the certainties are so vague even where everything seems to be written down, the interpretative picture gets even blurrier when one notes the disparity in style of the Months and their location in the baptistery. Their original position was different. The current one dates back to 1216, shortly after the Antelami construction site was completed, as the restoration by Bruno Zanardi has revealed. According to Chiara Frugoni, the cycle consisted of 16 statues (12 months and 4 seasons) for each of the internal sides of the baptistery. The critical hypothesis of the art historian Arturo Carlo Quintavalle, who sees Benedetto’s training in the Ile-de-France, is different. According to him, the Months are altorilievos planned for an exterior portal which was never completed, while the large slab of the Deposition, now walled up, must have been part of a pulpit that was never built.

Everything is open to interpretation, but this is precisely the charm of Medieval art, an ancient history that is not fixed and precise, distant from us in time, defined and blurry at once, an inspiring era whose influence persists today. Antelami’s figures are difficult to label. They have a terrestrial power, somewhat close to the Romanesque style; some of them, like June or November for example, are altered by an aerial sense of finesse that pushes them towards the Gothic style, but in all of them there is an absolute desire of Classicism. The figures of Antelami are the uninterrupted plot between the Romanesque Wiligelmo and the Renaissance Nicolò Pisano or Arnolfo da Cambio.

The extent of Benedetto Antelami’s innovation is such that his language spread like wildfire: from the reliefs of the Months for the portal of the Basilica of San Marco in Venice (about 1240), to the Lunette of the Magi in San Mercuriale in Forlì, to the cycle of the Master of the Months for the Cathedral of Ferrara. Antelami’s beautiful Deposition is also seminal. The figure of Christ in the center, while humanly collapsing, detached from the cross on the left, forms an arch which is contrasted by a flying buttress, that is the figure of Nicodemus who supports him as architecture, while Joseph of Arimathea releases the other hand. Two waves of movement start from this architectural juxtaposition of forces: a weaker one follows the procession of pious women on the left. On the right, a stronger crowd hinges on the round shield, ending with the Roman soldiers who cast lots for Jesus’ tunic. The linear rhythm changes, a phrasing of checks and balances between delicacy and violence. The cross rises in the centre, the only element that symbolically emerges from the squaring of the slab.

Examples of how influences from this piece can be found in the portal of the Cathedral of Ferrara by the Master of the Months, descending all the way down to Tuscany and Lazio in the wooden depositions of the cathedral of Volterra and that of Tivoli. Much later still, the same energy of contrasts between dark and light of bronze, that thickening of shadows on the face of Christ and the light on the diagonal arms that hold so humanly the heavy body, resonate in the bronze Deposition by Fausto Melotti from 1933. There is a poetry of the material that quivers, of the daily truth of a death that becomes lyrical, and the movement of a line that acts directly on the mass, runs through it, furrows it with its segments of tension, leading the light along the slippery floors, where a knotted rhythm tightens into a sacred emblem.

April 5, 2022