Some of Jean Katambayi Mukendi so far

Some the most salient aspects of the Jean Katambayi Mukendi’s art, between Lubumbashi, Brussels and New York

Our first encounter with the art of Jean Katambayi Mukendi was during a hot summer day in Brussels five years ago. From being one of the residents at WIELS a few months earlier, invited by his Lubumbashi fellow citizen Sammy Baloji, the Congolese artist was part of an exhibition at Gladstone Gallery. Kasper Bosmans was given the chance to take care of a summer show in the US gallery’s Belgian space, where he didn’t hesitate to include a couple of sculptures by Katambayi Mukendi in his finely curated collective exhibition titled The Hum Comes from the Stumuch.

[Here is the exhibition review. Ed.]

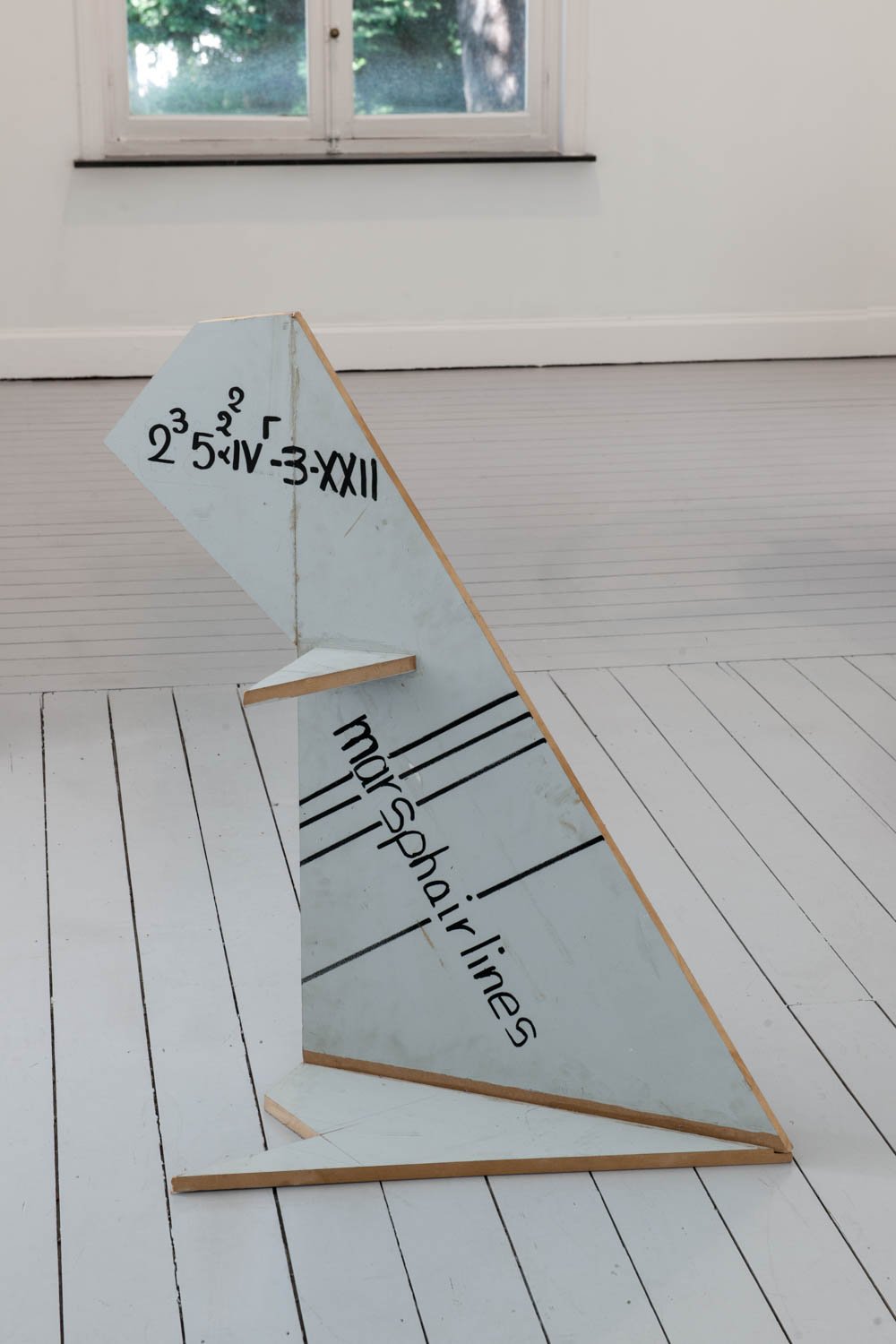

One of the works on display was especially interesting. A few MDF boards were cut, painted and assembled into an aircraft rudder, which included an airline logo as the corporate feature of a regular plane. Its grey hue gave it technological seriousness, contrasting with the handwritten logo. From that first encounter, the artwork kept coming back with all its questions and meanings, until recently we had the chance to unravel a bit of that mystery during a video call in French with the artist in Lubumbashi.

Jean Katambayi Mukendi spoke from his studio, which he kept on calling his own “museum of materials, where stuff has been accumulating for decades.” He told us that the invention of the airline Marsphairslines of the above mentioned artwork happened in the context of his own critique of nothing less than linear thinking. He told us: “A runaway might be straight, but the real runaway in life is not. To achieve some goals, we should not only have a direct approach. For example, we like to plan but then turbulences happen. When I create a plane, or even an airline that serves Mars [like Marsphairslines], what I am actually doing is to point to the importance of turbulence against linear thinking, maybe a reflection on political situations in Africa.”

With a firm voice, Jean Katambayi Mukendi spoke about ways of being ironic. He said: “When I worked as a math teacher in secondary school, people asked me why I was making all these jokes with my students. Math was supposed to be serious. I took it differently and it served us well. My artworks are similar. They might be ironic, but they address serious matters like the politics in Congo and the responsibility of foreign countries here.”

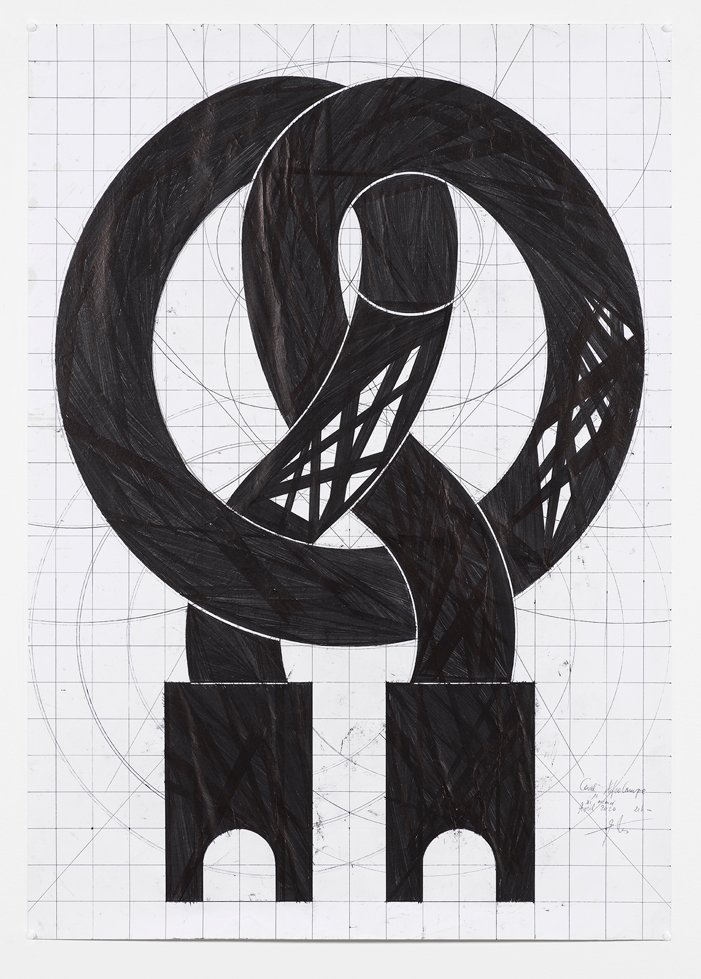

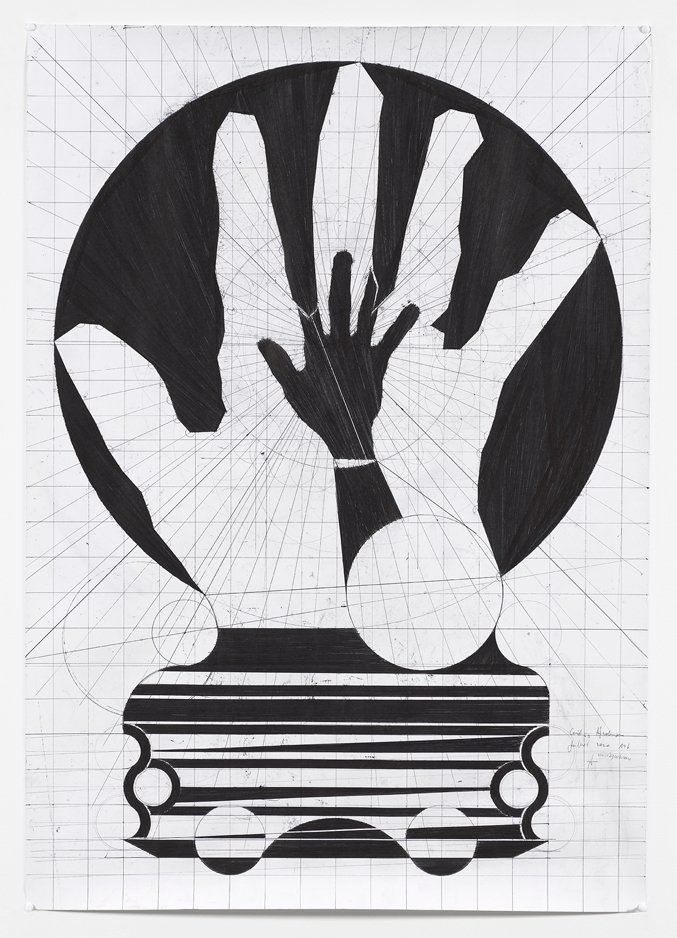

Sammi Baloji once mentioned that Lubumbashi is the city where first you have mining and then people. His collaborator at Picha Art and friend Jean Katambayi Mukendi brings this topic forward through the symbolic yet banal light bulb. The unremarkable gets charged. His paintings of light bulbs, inspired by technical drawings from the corporations that exploit his region, are more than just bizzaries of the Mannerist kind. They are true political pamphlets, conscious statements of an artist who is aware of the cognitive possibilities of aesthetically compelling images with a precise character.

Just like Covid vaccines, whose distribution reflects unfair inequalities on a global scale, so does the distribution of electricity in Lubumbashi. The artist told us: “Rich mining companies here always have stable electricity in their factories, whereas this is not the case for households, even those of the workers employed by those very companies. The population has taken matters in their own hands and they are now fixing cables or doing whatever they can to overcome the unjust behaviour of the power supply company.”

Jean Katambayi Mukendi is also a licensed electrician. He studied in a technical school that was established during the Belgian occupation to make sure European companies would never be short of cheap labour. To trace his art back to his education seems too simplistic though. Despite the technical and abstract look of his sculptures and drawings, Katambayi Mukendi’s art is down to earth, as the artist takes his current everyday life and struggles as a source material. For him, technology is a matter of form rather than function. There is more Lubumbashi than Mars in his pieces about flying into space. There is more political message than a display of technical knowledge. His art communicates real and political pragmatism, no matter its fantastic forms.

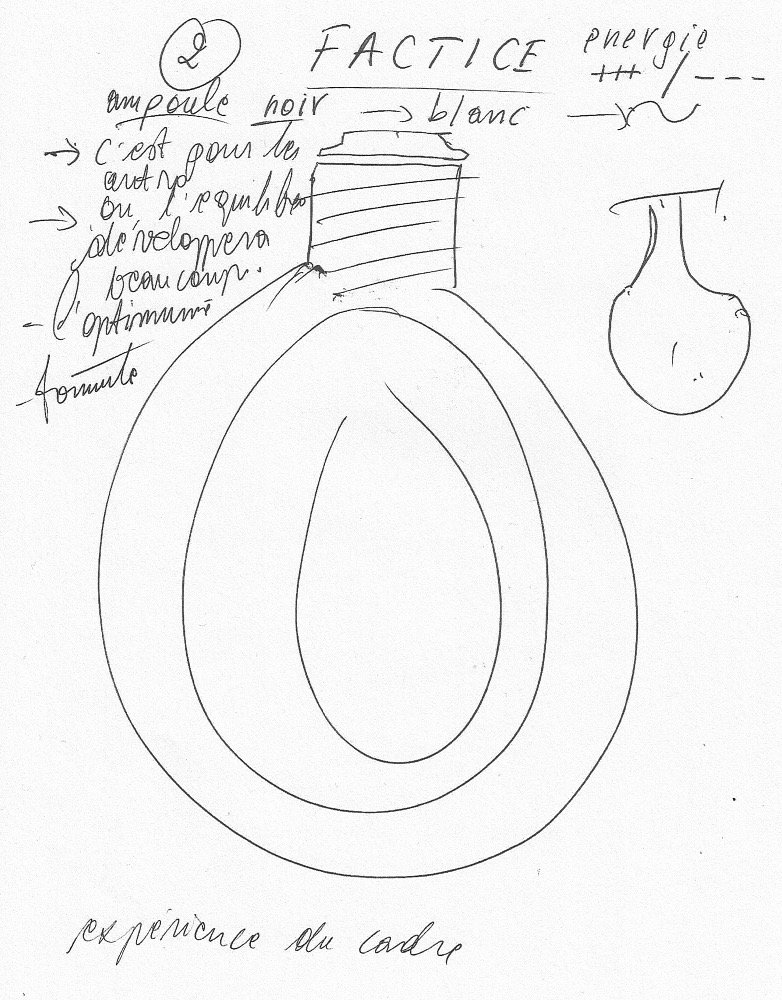

As to his move from a technical school to making art, he said: “My mother was somewhat of a visionary. She believed there was something more in life than falling into a place chosen for me by someone else, so she taught me that I had to study to understand life rather than to understand electricity.” In this regard, many of Jean Katambayi Mukendi’s preparatory sketches are full of directions: they are not so much instructions to fabricate an electric device, or solve a mathematical exercise, as they are annotations to real life.

Curator Caroline Dumalin writes that Katambayi invents an image of a world that has lost its structure. She comments on a series of annotated drawings, which came out of the artist residency in Brussels and were later edited by Simon Delobel into a publication called on ne sait pas où on va… mais on sait comment on va…. The thought process of the artist exposed by these drawings again confirms how the abstract can meet the real in his work. Formulas are there to hint at political conditions instead of mere numeric masturbation.

Jean Katambayi Mukendi recently had his first solo exhibition in the US. The New York gallery Ramiken Crucible gave him the opportunity to produce works in situ. When the pandemic made that impossible, the dealers showed a series of his Afrolamps he sent from Lubumbashi. This first experience in the US raises the question of how his work will be received in the American context in the long run. Political issues of racism in the US are clearly different from those in postcolonial Europe.

For example, the Middelheim Museum in Antwerp is putting up a show called Congoville, which will include a 3D version of Katambayi’s afrolamp and is supposedly part of an operation of self-reflection on Belgium’s colonial past. When a certain context such as the US lacks this discourse for historical or political reasons, one might ask how Katambayi’s work will be framed instead there. Time will tell.

March 24, 2021