Cassidy Toner, gambling as a career plan

Cassidy Toner stages repeated artistic misfires to better diffuse anxiety, pressure to perform, or the legibility of an artwork

In Seinfeld’s episode 7 of the second season, George Costanza quits his job after a hasty decision. Having the whole weekend to contemplate his impulsive announcement and, anxiety filling in, coming to regret it, he thinks of a way to solve the problem. The solution comes from his friend, Jerry Seinfeld, who advises George to go back to work on Monday, just as if nothing had happened. In the world of make-believe, reality can help ease anxiety. Something similar could be said of the work of Baltimore-born and Basel-based Cassidy Toner; her practice accommodates or anticipates feelings of shame, wrongdoings and deceptions, or acts that don’t fulfil their promises due to a cautious reluctance towards commitments.

In her clay sculptures of Wile E. Coyote, Toner stages the performance of trying to catch the Road Runner and the continual failure to do so. Her work hints at repetition elsewhere too, like dice that keep being thrown on the green carpet of a gambling table. In 2019, she took part in the Kiefer Hablitzel Göhner prize, a national Swiss competition for artists under 30 during and next to Art Basel, who have to show their works in individual booths in an art fair fashion. Toner was selected, presenting two paintings made of plexiglass and watercolor on paper that were gulped by a mysterious bronze-cast hand from behind the wall. In addition, a carpet installation was covering the floor of her booth, with a similar hand poking out of it, putting down a finger in a lofty manner. As the A.R. Ammons quote of the title recalled: One can’t have it both ways and both ways is the only way I want it.

Not having won one of the main prizes, she could apply to participate once more to the competition, which she did, taking part in next edition of 2021-2020 saw no exhibition in Basel due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This time, considering the expectations of a partially renewed jury to see a young artist evolving in the course of one year, hence hoping to see a new body of work, Toner instead decided to show exactly the same pieces in exactly the same booth, with only one difference: wallpapers made out of the official photographs of her previous presentation were glued to the walls and floor. Viewers would experience the same works, but in a poorer state; photographic reproductions printed on a wallpaper imperfectly glued, an unfortunate iteration.

This parasitical move produced a strange déjà vu, losing all its eerie feeling in favor of a bad joke when one recalled the 2019 edition-or would benefit from someone telling the story of that previous edition, suggesting the “you should have been there” sort of feeling from anecdotes that mainly traveled orally. Toner’s act resembled a stand up comedian telling a mediocre joke on stage, leaving that stage, and then coming back only to tell the same joke again with a red nose on. Repetition can precisely highlight the stage of any gesture. For Toner, it is not what causes the return of what has been, but rather a core principle to address the conditions in which it is executed, which were inherent to the art competition: pressure and desirability to win, expectations and productivity, legibility and jury logics. Moreover, the wallpaper of the previous body of work was a way to stage the new production in the frame of the old-fashioned one, maybe to better conjure it – the renewed presentation allowed Toner to win one of the main prizes. Here, anticipation is not a strategically efficient method, but only a way to gamble on a future state of mind. A work of art’s reception is indeed always dependent on the way the artist dissociates from it. Toner’s obsession for her own downfall is not really an act to preserve oneself from the potential shame of failure, but rather a way to address conditions of legibility. As she says, “You have to be careful how you die, it’s going to affect how people read your work”.

Through the use of tricks that test the limits of the context as one of negotiation, Toner riffs her way through pressures of performativity and efficiency, staging an act of non-cooperation that suggests a renewal of the logic of agency. [1] This in turn takes place in a contemporary era where artistic labor is part of an industry whose main currency is attention, modifying the meaning of artistic production: “The contemporary artist doesn’t just produce and present objects or images; he produces production itself, presentation itself…”. [2] Between an oppressive neo-liberal push for performance and the general status of an artistic production embedded in extensive creative networks, breaking the momentum can appear as a productive way to frame artistic production.

Toner’s interruption sheds light on the relationship between an artist and his/her own activity, shifting the focus from the conditions of realization to the inherent situation of any artwork. Art focuses on the displacement of attention and perception, insisting on the cognitive suitcases that we carry: the viewer who did see the previous Toner presentation will be treated differently than the one who didn’t, and in turn they will have another kind of experience from the one that didn’t hear the story. The gesture dissolves aesthetic experience in its situational parameters, opening the field to something left undone. A fallacious bootstrapping: Baron Munchausen freeing himself from quicksand by pulling on his own hair.

In 2019, for her solo presentation at Galerie Philippzollinger in Zurich, Toner pierced through the fourth wall between the artist’s atelier and the public realm of critical reception, unveiling this production of production through a display of rather self-critical attitudes.

Behind the wall and in the corner stood Wile E. Coyote Feels the Pang-of-Conscience. (How Do You Feel about Your Identity Being so Easily Reduced to this Caricature?). The Coyote seems to retire itself full of shame, fleeing from the cliché he created. The act of self-loathing and anthropomorphic assimilation to the artist – Toner repeating the coyote’s as the coyote himself repeats his unsuccessful traps – establishes links to Martin Kippenberg’s Martin, ab in die Ecke und schäm Dich of 1989/90.

But Toner’s reworking of Kippenberger’s shamefulness is less an iteration of an ironic subversion than a comment on those strategies as a way to trigger desire and consumption. Staging a similar coup, Toner presented in a duo-show with artist Rosa Aiello at Sgomento Zurigo a series of sculptures all titled I have a fetish for being judged, so get me off.

Based on kitsch figurines, these pieces were enlarged and produced as airbrush glazed ceramics, seemingly wanting to show off their artisanal quality. Toner added a series of words connected to the different animals through various systems of display, mainly arrows that would point back to them. Coming from a phrenology book (Vaught’s Practical Character Reader), they seemed to play at turn on an oversimplified moral topography of the world (“Heaven-Earth-Hell”), working as derogatory stamps for unproductive beings (“A Standard of Laziness”), or even acting as shaming associations, as when the Donkey figure is pointed at through a “Social Idiocy”. But those titles, stripped of any signifying context and exaggeratingly pointing at the ridiculously kitsch figures on which they act, lose their capacity to perform. Their meanings are emptied out, replaying the pseudo-scientific characteristic of their original enunciation. The works grant access to the joke without relying on a language pun but on the contrary, by ridiculing any assertion of meaning to those moral injunctions, constructing visual witticisms. As Toner, who started her studies in illustration before switching to visual arts, would say, these are works as “New Yorker cartoons for the illiterate”.

Her interest in permutable meanings is particularly strong in the series of Dust Bunnies, battery-driven balls made of fake fur picking up dust and other kinds of residues while nonchalantly rolling around their environment. Their names highlight logics of translatability, taking on different animal associations depending on the language, for example called sheep in French (moutons) or wool mice in German (Wollmäuse).

Those strange objects – one could think here of Meret Oppenheim’s exquisite compositions, only lacking the oneiric elevation – don’t operate solely as an agglomerate of life-filled materials; they also modify movements and behavior by moving through space, bumping into viewers or other artworks, and testing the peripheries of any exhibition context. They also role shift; Toner specifically recalled the New York gallerist Kai Matsumiya, who, having chosen to display the balls in the open situation of Nada art fair in Miami, and seeing the balls constantly roll out of his space, had to repeatedly kick them back in the booth, acting as a clumsy football player. Shifting roles is an effect of a tongue-in-cheek type of humor, blurring the location of the joke in a productive locked-down situation à la Andy Kaufmann. Mentioning artists such as Fischli & Weiss or Ursula Hodel, who all engaged with those kinds of gestures, Toner also suggests a link between this specific New-York comedy to a Swiss sense of humor, one that provokes uncertainty in the viewer, “when you’re not sure when to laugh, or where the joke is located,” as she said.

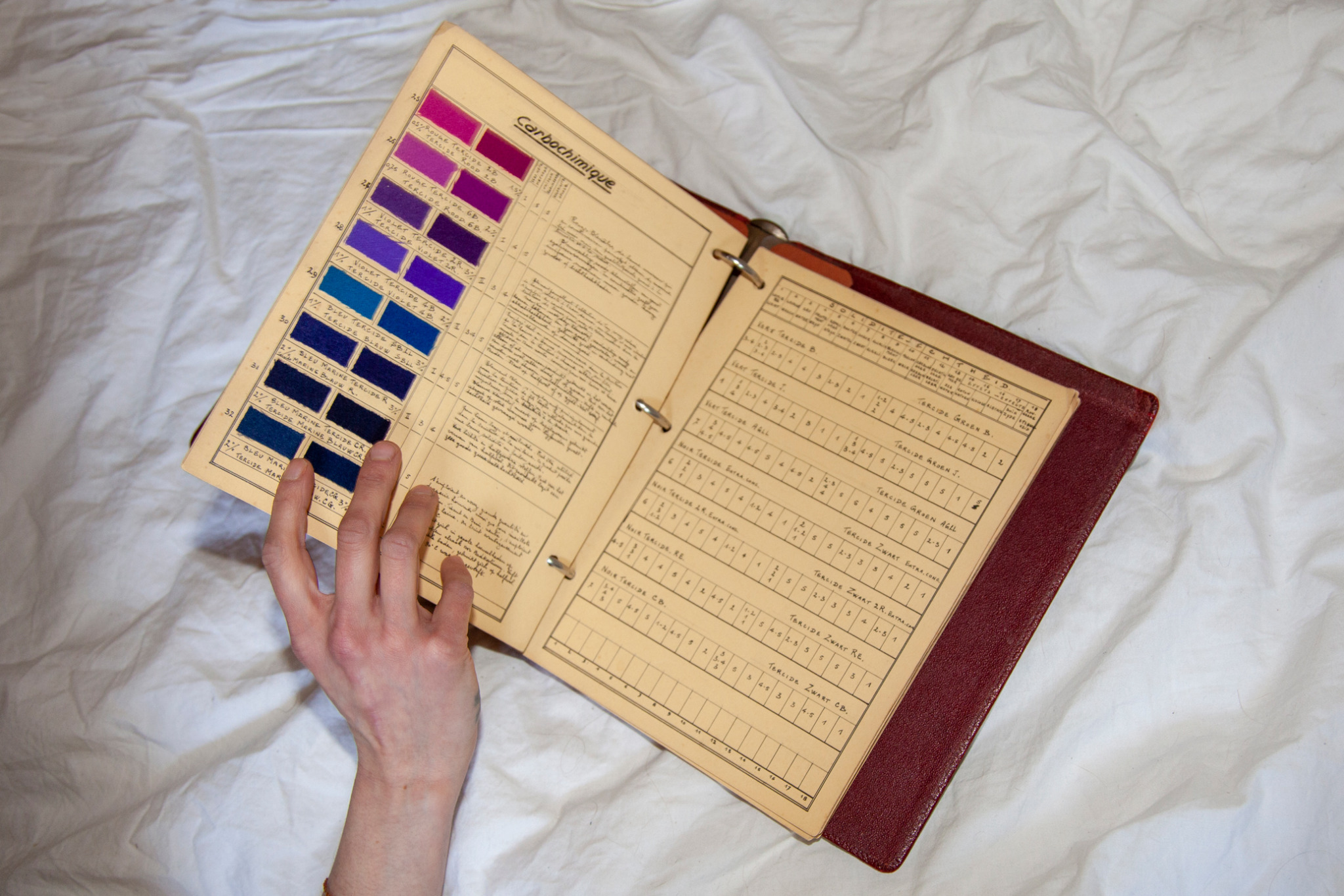

In 2017, Toner set up Rheum Room, an artist-run space set in (or rather “on”) the frame of her own bed in Basel. This peculiar setting is not indicated on its website, allowing for an intimate contract between her and the invited artists, asking for them to renegotiate her own relationship to this usually well-preserved space and the quality of her sleep. In March 2022, Belgian artist and Brussels memorabilia collector Jurgen Ots displayed a color theory book (accessible as a pdf through the website) explicating a large range of chemical transformations of coal in dyes. The insistence of this old-fashioned material process of color creation resonated with the symbolic perimeters of Rheum Room, the conditions of perception always being negotiated through a large array of inferences, either rational or chemical. Moreover, although the exhibitions should be viewable by appointment, no one seems to have visited any of them. Toner seems to never have time to open her space. This Kafkaesque setup blurs the purpose of the Duchampian boite-en-valise exhibition room, insisting on the fetish of the last residue of intimate space used as art display to better divert the expectations of a specific public. In the end, viewers of the exhibitions are made of friends crashing in her bed or passing-by lovers; a semi-attentive public. This setup of an audience unconsciously “playing dead” is to better subvert expectations of content and to insist on dynamics of desire; after all, it is also because no one saw Duchamp’s Fountain that it became such a mythical object.

In May 2022, Cassidy Toner will present her work at Castiglioni Fine Arts in Milan. The exhibition will play on the symbolism of the 1860 board game Game of Life, a familial recreation where destiny owes more to moral stature than sheer luck – the founder of the game specifically imagined a way of playing without dice. By performing rituals of chance, the artist will once again gamble her way through the logics of legibility, attempting to show that the best strategy to avoid failure is to double down.

During a recent visit to Toner’s studio, I spotted Lauren Berlant’s Cruel Optimism on the shelf. As an expression for the resentment of Americans in the late 2000s, “cruel optimism” refers to unreasonable desires, such that holding on to those desires is an obstacle to one’s flourishing. Since the 1980s and the disintegration of the social-democratic promise in the Western world, the general goal to attain the “good life” (for example job security and durable intimacy in our romantic lives) has degenerated into a mere fantasy, departed from reality. [3] In this context of generalized attrition and late-stage capitalism, where gambling is necessary only to stay in the game, Toner avoids waging her probability for success, preferring a path of contingency, conjuring the impacts of a stroke of luck or misfortune with a pair of loaded dice.

[1] Jan Verwoert, Exhaustion and Exuberance, Ways to Defy the Pressure to Perform, in: Jan Verwoert, Tell me What you Want, What you Really, Really Want (ed. Vanessa Ohiraun), Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2010

[2] John Kelsey, “Decapitsalim”; in: Rich Texts: Selected Writing for Art, Daniel Birnbaum and Isabelle Graw (eds.), Berlin: Sternberg press, 2010, p.68

[3] https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/03/25/affect-theory-and-the-new-age-of-anxiety

May 13, 2022