Identity, geography and gender in Aziza Kadyri’s practice

Aziza Kadyri delves into the fluidity of her origins, transforming memory into a functional emotion.

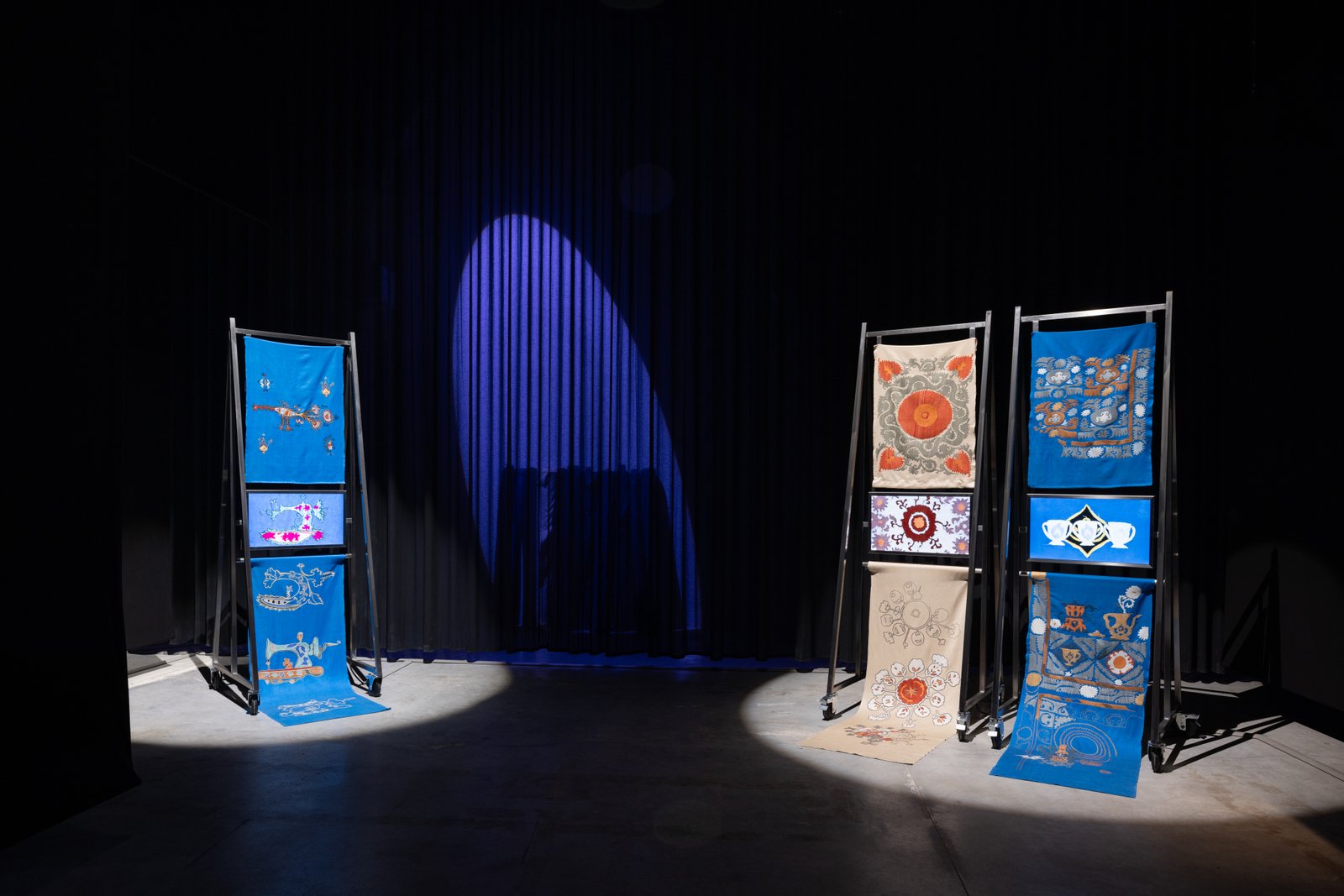

Born in Russia in 1994, Aziza Kadyri represented Uzbekistan, her home country, at the 60th Venice Biennale, a celebration of the ‘Foreigners Everywhere’. As we write, her works are on display at the Pushkin House in London (in a solo show curated by the writer) and at Eastcontemporary in Milan. We interviewed her to delve deeper into her approach to artistic creation, starting with the materials she selects, particularly fabric scraps, whose fluidity aligns perfectly with Aziza Kadyri’s most cherished themes. Her works stem from unconscious memories and emotions, family and personal stories with a strong political flavor, emotional maps of the places she has lived, and identity transformations. These are just a few of the concepts that emerge from her practice, through which Aziza aims to reshape the world with the power of her ideas.

What questions are you asking yourself in the current artistic research? What are you incredibly excited about?

Aziza Kadyri: Right now, my artistic research is full of questions that I don’t necessarily have answers to – mostly about how I process my own memories, subconscious thoughts, and emotional responses. I’m exploring how diving deeper into these introspective areas might help me develop an alter ego – someone who can embody the trickster figures I’m researching and hopefully expand into a performance practice. I’m gradually finding my way back to the days of performing.

I’ve also started exploring the possibilities of responsive textiles, especially through my residency at Somerset House and UAL Creative Computing Institute. The idea of creating textiles or installations that react to touch, movement, or sound is exciting because it’s such a dynamic way to bring audiences into the work. But honestly, this year has been so intense, and while excitement has been harder to come by, I’m focusing on making space to reconnect with why I started doing all of this in the first place.

I’ve got a commission about Zeppelins that I’m actually looking forward to. It’s so completely outside of my usual practice that it feels refreshing – like stepping into a totally different headspace. On top of that, there’s a public art commission back in Uzbekistan from the inaugural Bukhara Biennial, which feels like a dream come true since I’ve always wanted to explore public art. I think that’s what I need right now: something unexpected and far enough from the themes I’m always tackling to remind me what it’s like to just play creatively.

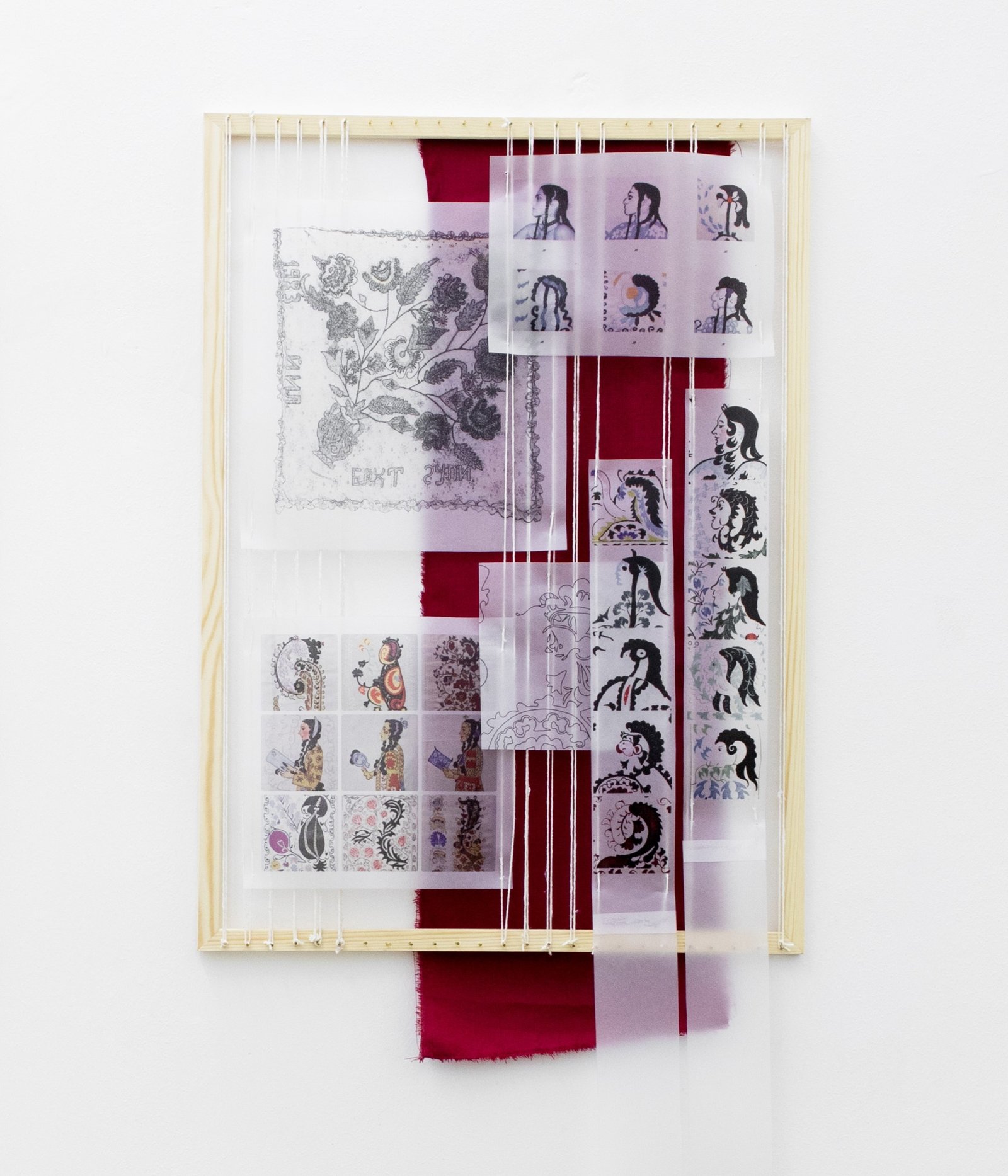

For the exhibition at the Pushkin House, which can more appropriately be called an intervention into an architecturally complex space, you made the first ‘belbog’ pieces — based on the readymade men’s traditional Uzbek belts. By using them as frames for personal ‘coats of arms’ in relation to the cities which partially shaped your identity, you radically repurposed and ‘unlifted’ this vernacular utilitarian object. What are this action’s crucial tenets for you— artistically and conceptually?

Aziza Kadyri: These pieces originate from my ongoing practice of working with found and salvaged textiles, often sourced from vintage market vendors who now recognise me as a regular. These textiles, created during the Soviet 70s and 80s, hold a layered and contradictory history. They are mass-produced interpretations of tradition – machine-embroidered designs that hint at familiar shapes but fail to capture the essence of original craftsmanship. The sashes I used were utilitarian, strikingly red, like a pioneer’s (a member of the official Soviet youth movement) tie, with a thin ornamental border and an empty center. This void called out to me, demanding a narrative–something deeply personal. As the eldest daughter, who had to take on many responsibilities, I often joke that I’m the family’s desired eldest ‘son’. Taking this traditionally masculine object and bending it to fit my story became an act of reclaiming and reimagining the normalised societal hierarchies.

These ‘coats of arms’ are, for me, a form of psychogeography. They map my emotional journeys through cities that have shaped my identity: Taipei, Moscow, Beijing, Tashkent. Each piece reflects a subjective, autobiographical impression of these places, rendered through an imaginative series of ‘balancing acts’. There’s metaphor and magical realism at play – a reflection of my inner ‘circus’, where I continuously take on the role of a trickster in its original sense: a storyteller and magician. While the term ‘coats of arms’ works beautifully, I envisioned them more as circus adverts or banners, capturing the ever playful, performative nature of my process.

Ultimately, this work is about transformation – turning utilitarian objects with mixed histories into frames for deeply personal narratives. It’s a balancing act between the personal and the collective, the traditional and the contemporary, the masculine and the feminine. The intervention at Pushkin House was an invitation to engage with these tensions and to challenge the ways in which objects and stories are allowed to evolve.

Storytelling is inherently essential for your practice as a whole. You are also a pretty great speaker. What is (or are) your favourite media for expressing feelings and ideas?

Aziza Kadyri: I come from a background of theatre and live performance, and these media consistently find their way into every single project I do. I work really well with the media that leave space for chance, error, and deviation – the media that allow for more intuitive, improvised creation. Textiles can be sewn together but also unpicked and rearranged on the spot; they are flexible, adaptable, and interact differently with each viewer. The same goes for performance – it depends so much on the dialogue with the audience, and magic is created in the interactions and connections. All the things that go off script are the best part. I thrive in designing emotional experiences through multi-dimensional interactivity and physical presence. I think that’s why I find it hard to connect with forms like film and painting – they require precise planning and don’t allow for much changes or spontaneity once they’re complete. Although, I like making somewhat chaotic video work.

How do you negotiate your practice’s inward and individual dimensions with the more significant questions of politics which emerge from your work?

Aziza Kadyri: For me, the personal, familial, and collective are inseparable. My own experiences,how I see the world and interact with it,are shaped by the political realities I’ve lived through. When I dig into my personal or family stories, I often find they echo much larger political issues: migration, gender, power dynamics, identity. So, the process feels less like balancing two different things and more like revealing how they’re interconnected.

In my practice, I consciously lean into the personal, the very specific, because it’s a way of making bigger, more abstract socio-political ideas feel tangible. People tend to relate to stories. They see themselves in them, even if the context is unfamiliar – this is something I witnessed in the reactions to the Uzbekistan Pavilion in Venice this year. But I’m also aware that these personal narratives don’t exist in a vacuum – they’re shaped by systems, histories, and inequalities, and I want that to be visible in my work.

At the same time, I’m careful not to flatten the personal into pure symbolism for political critique. I think there’s power in letting the deeply individual exist for what it is – messy, emotional, human – while allowing the politics to emerge from it naturally.

Your practice, at large, deals with the question of fluidity of identity. Born in Moscow, growing up between there and Tashkent, studying in Shanghai and Taiwan and currently living in London — and representing Uzbekistan in the Biennale without being able to access the national archives, essential for your work and research due to the lack of an Uzbek passport. How do you negotiate a complex position of your own identity?

Aziza Kadyri: I don’t have a clear answer to the question of my identity. It’s something I’m still trying to make sense of, and my art is one of the ways I try to work through it. I navigate my culture both as an ‘insider’ – shaped by family and friends – and as an ‘outsider’, a diasporic individual who has spent much of my life in Taiwan, Mainland China, Russia, and the UK. I have lived on my own since I was 17, and easily adapting to new environments is one of my main skills. I feel like a mediator and connector of many ideas and disparate stories, which are a collection of fun fragments, a living cabinet of curiosities.

Not being able to access history records highlights the tension between being tied to a place through culture, memory, and heritage, but being excluded in other ways – legally or institutionally. Rather than seeing this as a limitation, as a hopeless optimist, I try to use it as a creative force. When official systems or archives are out of reach, I turn to oral histories, personal memory, and collaboration with others to construct alternative narratives. This is where the concept of ‘critical fabulation’ comes into play – reimagining history when access to its records is restricted.

“Tricking” systems is an essential skill for any artist. Your interest in tricksters is, therefore, more than natural. Who are your favourite ones in history and mythology, and why?

Aziza Kadyri: One of the most significant figures is Nasreddin Khoja, the Central Asian and Middle Eastern trickster. I grew up hearing endless stories and fables, in which he’s portrayed as both a fool and a wise man, using humor and paradox to uncover deeper truths about human nature. His ability to navigate social and moral complexities through seemingly simple acts has left a lasting impression on how I see storytelling as a tool for critique.

Another is Sun Wukong, the Monkey King from the 16th-century Chinese classic Journey to the West, who influenced me deeply during my teenage years, as well as through my connection to China. He’s a quintessential trickster – mischievous, a shape-shifter, a situation-inverter; constantly pushing boundaries and challenging authority. His story illustrates the value of persistence and wit in the face of immense obstacles.

Lastly, Scheherazade from One Thousand and One Nights is an important example of the female trickster, or as Marilyn Jurich calls her, a “trickstar.” As Jurich explains in Scheherazade’s Sisters: Trickster Heroines and Their Stories in World Literature, trickstars use verbal facility, psychological acuity, and diplomatic know-how to outwit oppressive systems. Scheherazade’s ability to craft captivating stories not only saves her own life but also somewhat transforms the violent patriarchal system she’s trapped in. It’s a benevolent kind of trickster: a culture bringer, a transformer, an ‘alchemist’ – but trickstering born out of necessity and circumstance rather than pure choice or her own volition.

What ties these figures together – and what inspires me most – is how they use their resourcefulness and creativity to reshape the worlds they inhabit. Trickery isn’t just about deception; it’s about finding ways to navigate and transform systems by being adaptive, open-minded, by not seeing the world as strictly black and white and not dealing in absolutes. That’s the energy I try to bring into my own practice.

December 12, 2024