Nandi Loaf: experience, participation, fetishization

Nandi Loaf lures exhibition goers into an arena of participation, which in itself becomes a charged variable for the artist to work with and against.

Nandi Loaf’s is a project of positioning. Her practice revolves around situating one or more variables within a locale predisposed to artistic over-explanation and hyper-commodification. Loaf deposits her viewers into a network of variables. This practice is not made up of rivers leading to the ocean, it’s the ocean itself. That being said, there are no traces of concrete resolutions, nor heady platitudes. Nothing is fixed, but rather open signifiers hang in limbo, agitated by the viewer’s input. Loaf, invested in the greater machine, lures exhibition goers into an arena of participation, which in itself becomes a charged variable for the artist to work with and against.

The artist is a stage technician of sorts, whose presence is made scarce once the curtain rises and the action commences. To collate estranged, and perhaps random, forms and ideas into one somewhat homogenous landscape, that is the project. Oftentimes, the viewer-performer confuses despair with elation, submitting to a bacchanalia of warped emotions, Nandi Loaf watches as participation folds on itself, over and over again until the original kernel is unrecognizable and toward the point of entropic collapse.

King’s Leap is Loaf’s primary gallery. The owner, Alec Petty, consistently deals with the artist’s work and, as such, becomes complicit in the performance that she designs. He must constantly observe and negotiate his own role, explaining “in every circumstance that we collaborate, Nandi finds a new way for me to activate her work.” Petty continues, “because her work is so often about confronting what it means to be an artist dealing in the industry’s muck, the aesthetics of her practice become the actual labour at the site of the gallery.” He’s by no means the author, but without his station within the matrix, these shows simply wouldn’t function in the same manner.

Nandi Loaf’s most recent solo exhibition King’s Leap opened in September of 2024. Titled “Ever,” this show unleashed the artist’s characteristic theater of absurdity. Petty maintains that “it’s very carefully conceived that all of the narrative beats hit when they are meant to hit.” The ground floor, completely transformed, consisted of frosted windows and overhead lights covered in vinyl, all contributing to the impression of a fetish nightclub. On the opening night, a cast of maids handed out lambrusco, Fireball shots, and cookies that read “WE LOVE YOU NANDI” as the invite-only guests rolled in and through Loaf’s set. Another gallery artist was stationed as the door man, adhering to Loaf’s instruction to only allow five people at a time. Through a doorway and into the back room, one could find a small spout leaking red fluid, i.e. slowly bleeding.

One of the foremost operations during this event was that guests were required to sign Funko POP! toys, which functioned as the visitors’ book. This was a move to activate the toys, which the artist would later seal in acrylic boxes and situate on a set of empty pedestals downstairs. Moving down into the basement, another maid offered more shots of Fireball as people looked over the temporarily vacant plots. After the opening, this space would be sealed off to everyone except for “art world professionals,” i.e. those who identified as collectors, curators, or writers.

The Funko POP! objects, carefully considered by Loaf, resonate due to their clear associations with the art object: collectible, tradeable, fetishizable. As Petty elucidates, the artist recognizes that although “we are in hell, [she] has to work within the constraints of the circumstances. And through that she can find novel solutions to aesthetic problems.” The toys are the perfect response to these conditions. Petty goes on, “these commercial goods that evade discreet relationships to high or low aesthetics and value,” relate directly the “conditional-material base of the work, which is the over-saturated, doom market, doom scroll of our moment.”

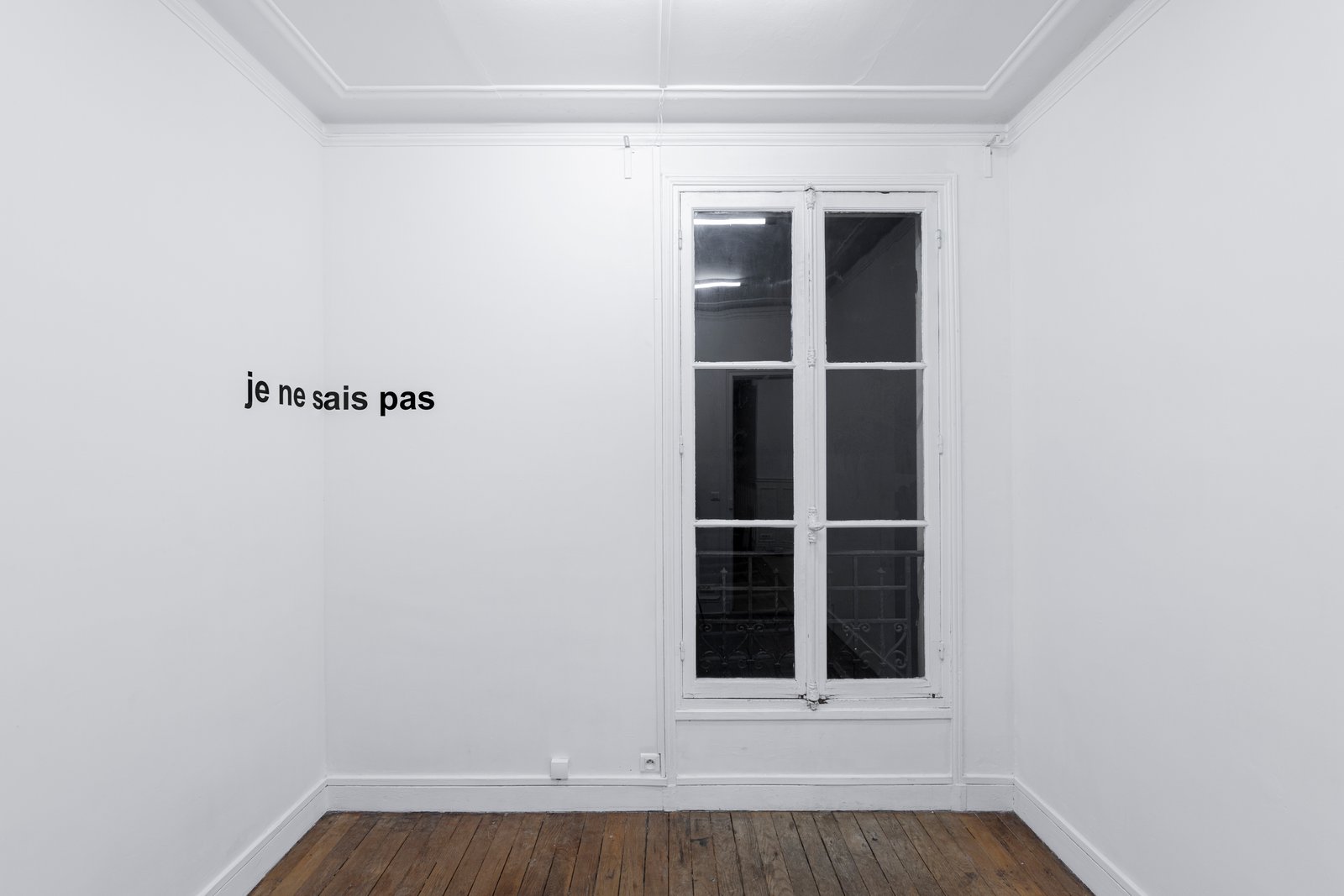

For an earlier exhibition at Profil in Paris, Loaf’s machinations were organized sparingly. Two wall works clung to the room’s corners, displaying alternate languages in the artist’s characteristic bolded Helvetica font. The one printed in vinyl declares “je ne sais pas” (“I don’t know” in English). Another, hand-painted counterpoint is intended to read “there is no spectacle” in Japanese, but could be translated to “there is no show,” “the show is over,” or some other variation depending on the machine or viewer. The script is accompanied by Jack Skellington in Santa Claus garb, incorporated without any claim to meaning. Visitors could also experience an auditory audio piece that consists of Loaf’s absurdist document, chock full of numbers and nonsense, converted from text-to-speech. All of these moves reduced the space to pure experience, participation, and, yet again, fetishization.

Early yet, Nandi Loaf orchestrated another stripped down playing field at Sebastian Gladstone in Los Angeles, which revolved around a singular installation of aluminum-mounted photographs. The presentation, referred to as “Lot 99,” is reminiscent of Rosemarie Trockel’s “Cluster” series, which consists of variable images organized into rectangular display systems. In a catalogue essay for the artist’s survey at Moderna Museet Malmö, Jo Applin relates this work to Trockel’s practice, positing that it “embodies this conceptual-material matrix,” and also “produces not one authorial voice but a polyvocal play, a cacophony, into which we can tune in, but also out, as though a radio frequency that is hard to find.” Applin goes further, writing “The sheer eccentricity and disconnectedness of the photographs in her cluster groupings compels viewers to seek out connecting lines running through their disparate subject matter, a perverse drive to impose order on disorder, to see closure to the series’ open ended aspect.”

These conceptual nodes should, at this point, sound familiar, clearly resonating with those of Loaf’s project. She and Trockel align in their shared presentations of unfixed narrative prospects and elisions of resolution. Their coordination of images are congruous, but positioned in different conceptual terrains, both cataloguing materials from anywhere and depositing them into disparate environments. The landscape in which Nandi Loaf operates, however, is one that speaks constantly and directly to the art industrial complex. Petty asserts that “by taking you through this very heightened and elaborate and elongated [situation], she enforces that the actual machine of the practice is the staging and our experience of how an exhibition functions.”

February 26, 2025