Laura Owens: a mid-career interview

‘I wouldn’t be bored if I became an artist because there’s always a question and never an answer’. So thought Laura Owens when she was 14. Now the Whitney Museum is dedicating her a comprehensive solo show. Is that also a question for her?

- Laura Owens in her Los Angeles studio. Courtesy the artist.

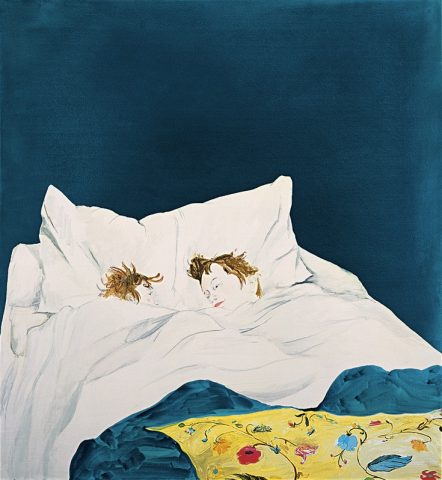

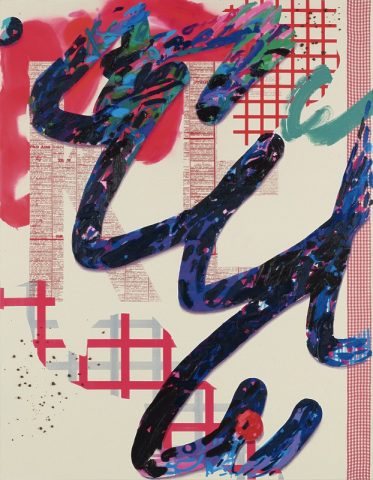

- Laura Owens, Untitled, 1997. Acrylic and oil on canvas, 78 × 84 in. (198.1 × 213.4 cm). Collection of Mima and César Reyes. © Laura Owens.

- Laura Owens, Untitled, 2000. Acrylic, oil, and graphite on canvas, 72 × 66 1/2 in. (182.9 × 168.9 cm). Collezione Giuseppe Iannaccone, Milan. © Laura Owens.

- Laura Owens, Untitled, 1997. Oil, acrylic, and airbrushed oil on canvas, 96 × 120 in. (243.8 × 304.8 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; promised gift of Thea Westreich Wagner and Ethan Wagner P.2011.274. © Laura Owens.

- Laura Owens, Untitled, 1998. Acrylic on canvas, 66 × 72 in. (167.6 × 182.9 cm). Collection of the artist. Courtesy the artist / Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, New York and Rome; Sadie Coles HQ, London; and Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne. © Laura Owens.

- Laura Owens, Untitled, 2006. Acrylic and oil on linen, 29 1/4 × 21 1/4 in. (74.3 × 54 cm). Collection Florence and Philippe Ségalot, New York. © Laura Owens.

- Laura Owens, Untitled, 2012. Acrylic, oil, vinyl paint, resin, pumice, and fabric on canvas, 108 × 84 in. (274.3 × 213.4 cm). Collection of the artist. Courtesy the artist / Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, New York and Rome; Sadie Coles HQ, London; and Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne. © Laura Owens.

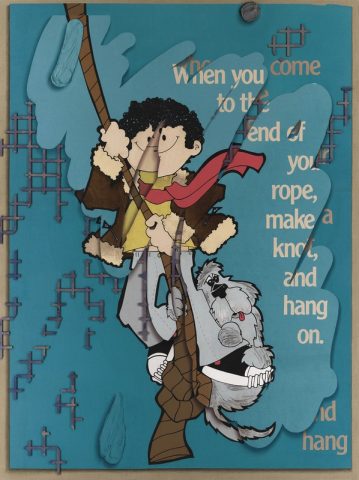

- Laura Owens, Untitled, 2014. Ink, silkscreen ink, vinyl paint, acrylic, oil, pastel, paper, wood, solvent transfers, stickers, handmade paper, thread, board, and glue on linen and polyester, five parts: 138 1/8 × 106 ½ x 2 5/8 in. (350.8 × 270.5 × 6.7 cm) overall. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from Jonathan Sobel 2014.281a-e. © Laura Owens.

- Laura Owens, Untitled, 2004. Acrylic and oil on linen, 66 × 66 in. (167.6 × 167.6 cm). Collection of Nina Moore. © Laura Owens.

- Laura Owens, Untitled, 2006. Acrylic and oil on linen, 56 × 40 in. (142.2 × 101.6 cm). Charlotte Feng Ford Collection. © Laura Owens.

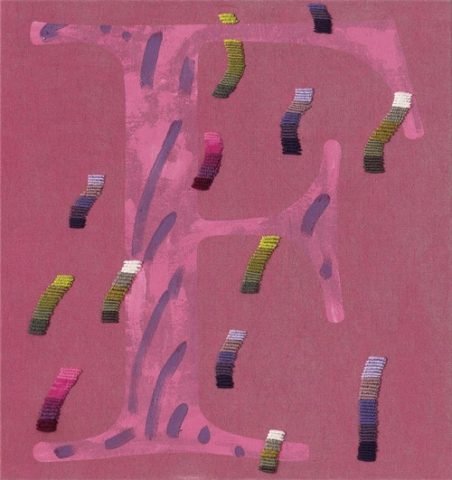

- Detail of Laura Owens, Untitled, 2012. Acrylic, oil, vinyl paint, charcoal, yarn, and cord on hand-dyed linen, 33 panels, 35 1/2 × 33 1/4 in. (90.2 × 84.5 cm) each. Collection of Maja Hoffmann/LUMA Foundation. © Laura Owens.

- Detail of Laura Owens, Untitled, 2012. Acrylic, oil, vinyl paint, charcoal, yarn, and cord on hand-dyed linen, 33 panels, 35 1/2 × 33 1/4 in. (90.2 × 84.5 cm) each. Collection of Maja Hoffmann/LUMA Foundation. © Laura Owens.

- Detail of Laura Owens, Untitled, 2012. Acrylic, oil, vinyl paint, charcoal, yarn, and cord on hand-dyed linen, 33 panels, 35 1/2 × 33 1/4 in. (90.2 × 84.5 cm) each. Collection of Maja Hoffmann/LUMA Foundation. © Laura Owens.

Mining the history of painting while exploring the boundaries between representation and abstraction, Laura Owens employs a diverse source of references in her captivating paintings. Born in Ohio and educated at the Rhode Island School of Design and Cal Arts, the painter has lived and worked in Los Angeles for more than 20 years. The subject of a mid-career retrospective at the Whitney that opened this week, Owens recently sat down with Conceptual Fine Arts at the museum to discuss the wide-ranging body of work in the exhibition.

What motivated you to become an artist?

Laura Owens: I was around 14, living in Norwalk, Ohio, and doing pretty good in school. I remember thinking that I wouldn’t be bored if I became an artist because there’s always a question and never an answer—it’s a lifelong search. I later had a crush on a guy that was going to the Cleveland Institute of the Arts and he became my boyfriend. I was going up there and hanging out with artists. I was in the punk rock scene and going to see shows and alternative theater. Basically, I was trying to get out of Ohio.

What was your first big break?

Laura Owens: In Norwalk, I met a kid who was a model and an actor and his mom had sent him to Interlochen Center for the Arts. He came back and talked about how cool it was and I was listening and asked if they had art there and he said yeah. I looked into it and decided that I wanted to go there, but there was no way my parents could afford to send me. However, the summer art camp was around $2500 I told my father that I had to go and he was going to pay for it. One of my teachers was Tom Mills, a professor at the Rhode Island School of Design. I did figure drawings at Interlochen all day and my skills greatly improved. My teacher was on the application committee at RISD and said I should apply. He told me what the portfolio should look like. Had I not gone to Interlochen I would not have known about RISD or even been accepted because I wouldn’t have had the figure drawing portfolio to get in.

What inspired you to stick with it in the early days when you had to balance the struggle to stay afloat financially with a need to establish your own voice?

Laura Owens: I really never had any wavering. I just tried to figure out how to make it work. It was the 1990s and for whatever reason American Express was handing out credit cards. People were making indie films on credit so I got a few credits cards and found a storefront in Eagle Rock for $300 a month that I could live in and I took out loans so that I could go to Cal Arts. I just did it. I knew that I was going to do it and somehow I managed. I didn’t have any parental support, other than my mom coming out and helping me with my paintings, but she wouldn’t give me any money.

Do you think you think staying in Los Angeles impacted your development?

Laura Owens: Definitely, I made a conscious choice to stay after I finished school. I had friends and there’s a kind of quasi-academic scene coming out of Cal Arts and Art Center that remains supportive for a while. It was a small scene where you felt like you knew everyone, and it was accessible. You’d go to an opening and John Baldessari would be there. It would be like, oh there’s Baldessari. It wasn’t like an unobtainable relationship. Dave Muller was doing his “Three Day Weekend” events and Frances Stark, Sharon Lockhart and I were exhibiting in them. It was one of my first opportunities to show.

How has your path to painting evolved?

Laura Owens: I’ve gotten more confident.

Has collaboration played a role in that evolution?

Definitely, every time I collaborate the toolbox that’s accessible to me doubles. That stays with me even after the collaboration. Before I collaborated with Scott Reeder I had a rule about painting—I was never going to add collage to the canvas. We did a painting together and he just cut something out and stuck it on it. I was like wait, what, you can’t do that. Then I was like okay, I can break that rule. Now I’m done with it.

Is curating a part of that aspect of collaboration or do you see it as a different activity?

There’s a selfish aspect to curating, one where I get to watch how other people make decisions installing and editing their work. By seeing that happen I learn about my own habits and predispositions—and how they’re just based on insecurities. Other people have insecurities, but they’re not mine. I see what they’re doing and it gives me permission. Sometimes I curate because I think we should be looking at someone’s work. If I’m looking at this work then you should be looking at it. Let’s be supportive of this person, because it seems like they’re on to something.

I’ve read that you tend to get your best work done in the studio between 10 pm and 3 am. What is it about these bewitching hours that bring out the most in you?

It’s literally that my kids are asleep and it’s when people aren’t supposed to call you. It’s finally this moment when you don’t feel like you have to do something else—you’re off the hook. Plus I do think there’s something to be said about being a little bit tired when you work. It makes decisions a little less fraught. Inhibitions go away, but it’s probably the quietness.

Are you trying to make good art or take risks?

I probably lean toward the second choice. It’s probably more that I’m trying to show myself something that I haven’t seen before. Sometime it’s confusing to me. It’s up in the air as to whether it’s going to be any good or not. If there’s something in me that’s trying to make it good, it’s not on the surface. I think it’s more buried down inside.

Is your work speculative?

Sometimes, yeah, I would think that it is.

Do you consider yourself an abstract painter or a figurative one?

I sort of see everything in terms of abstraction, but you can see it in terms of documentation or realism, too. It’s not the binary that really applies. I feel like it makes it reductive when you chose. A Jasper Johns’ “Flag” painting is abstract to me, because it’s not in any kind of perspective space.

Why are all of your works titled Untitled?

At RISD I made some really bad titles. Looking back on it, it was something that I thought was a good idea and later realized that the title sucked. There are code words to reference them, but somewhere along the line I was in a museum show and a code for one of the pieces ended up on the title card. I had to tell the curator that it was just “Untitled.”

In 1994 you made a list for “How to Be the Best Artist in the World” and another one called “What My Paintings Mean to Me.” How has this kind of self-analysis been helpful to you and your art-making?

I was 24 years old. It was note taking in a sketchbook in the studio alone. I think it was just about trying to be brave and believe that you can do whatever you want. I would often make lists of artists that I liked or aspired to be the friend of, even if they are dead.

In his essay for your 2003 survey at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles the show’s curator Paul Schimmel used a ping-pong metaphor for your bouncing back and forth across art movements, histories, styles and ideologies. Is that an accurate account of your practice?

I try to do a sort of tabula rasa before I start again, but I’m certainly influenced by different forms of art and non-art. I guess I have a philosophy that more is better, where all of it kind of filters in.

Are you working from imagination or mediated sources?

Both.

How diverse are your sources, both for subjects of your paintings and for style?

They’re quite diverse. For example, in one series of paintings that I did I was getting spam emails that you would normally delete, but I decided this was free material and started using the messages in my paintings. You try to bring up what’s being repressed. You try to bring that up and let it be in the open air. Anytime I feel that I’m leaving the figure out of the painting I’m like okay we got to bring that up to the surface—let’s try to paint the figure again.

What influences your palette?

I used to just go to the paint store and pick-out palettes that designers used or pick-up a greeting card and say this is my palette. If Martha Stewart makes a palette for Home Depot you can just take that. You can lift it for a painting—just appropriate her palette.

What’s your fascination with scale?

I like both big and small. They’re both useful. You can do different things with them, so why not?

In the 2015 exhibition Painting After Technology at Tate Modern the curator Mark Godfrey draws a parallel between artists like Sigmar Polke, Albert Oehlen, Charline von Heyl, Tomma Abts and yourself who make work that relates to how we use screens of digital devices. How do you see your use of layering in relationship to this idea?

I use some painter programs where you build your image with layers. You name the layers and they’re in your sidebar. I started using computers in the early ‘90s to just get through choices that I’d have to make in the painting with color. When I started doing etchings and other kinds of printmaking I realized that the people who had built that software were building it out of a conceptual construct that came out of printmaking. From that point on it just became an extension of printmaking for me. Whoever designed Photoshop and these programs, where there are CMYK channels, understood that the basic ideas of etching were that you’re color combining with plates. I just see it as an extension of that process, rather than a break with history.

What led you to create 356 S Mission Road, your gallery-cum-studio, or maybe vice versa?

I looked around for several years for a space that could be a studio and that would then become an exhibition. The intention was just to do the one show, which I did. But what happened was that we started doing performances during my show and there was as a natural progression afterward.

How does the architecture of the gallery space impact the show that you make for it?

I sat in that space for six months and came up with about 20 different ideas for what I would do—build walls or not build walls and what about the scale? In other works I’ve sometimes taken aspects of the site to start the painting. I have a hard time starting. I really need some kind of kernel to get going and the space could be the kernel—something to focus my ideas.

What kind of overview of your work have you and curator Scott Rothkoph created for the Whitney Museum exhibition?

We’re going to show a lot of work, but we’re going to specifically show select ideas—like the project-based nature of some of the shows and how the site often had a real specific relationship to the installation. We’re also going to show how certain paintings were made to respond to each other and when they get dispersed they lose that quality but when you bring them back together it reanimates the initial conversation. I was influenced by artists like Jorge Pardo and that kind of relational aesthetics’ moment when I was making the first survey show at MOCA, and the social and anecdotal became part of the work.

If a viewer was new to your work, what’s the one painting or series of works that you would say they had to see in the show?

It’s hard to say, but I guess I would take them up to the 8th floor, where we are installing a five-panel painting. It’s a recreation of my 2015 show at Capitain Petzel in Berlin. There’s a particular point of view for it, where everything comes together. The paintings become sculptures, and it’s a bizarre kind of encounter. You wouldn’t think that an artist who paints the figure and did this other kind of stuff, too. It will give the viewer a good introduction to what goes on in my mind.

Your 664-page catalogue functions like an archive, a diary and an instructional book on how to become a successful artist. What was your goal in painstakingly constructing it?

When we started thinking about what would be in the show we realized that there wouldn’t be enough room to show it all. And when I thought about me making something new for the show I knew that we would have to eliminate something for it to fit, so I said I’m not making any new work. I put all of the energy that would go into making new work into the catalogue, which has 8,000 unique covers. It’s the kind of project that shows what happens when you lay bare what it took to get from Norwalk, Ohio to the Whitney Museum of American Art. There’s so much about being an artist that just isn’t talked about. It is a struggle to keep doing it. Maybe a young artist working in Kansas, or even in India, will find it interesting.

In your notes for the book you ask, “Why make art?” and “What is a painting?” Have you found the answers to those questions or are you still looking?

I feel like I periodically answer these questions and it keeps me going. But I have to keep asking again and again. There are a lot of reasons in the world to feel hopeless. Letting your self take the time to get depressed about the fact that there might not be any reason to make art and then coming out of that depression and finding a reason to make it again is what we have to do. At other times I ask myself, “Why not make paintings?”

March 14, 2020