In dialogue with Nick Darmstaedter and his visual manipulation of masculinity in 1972

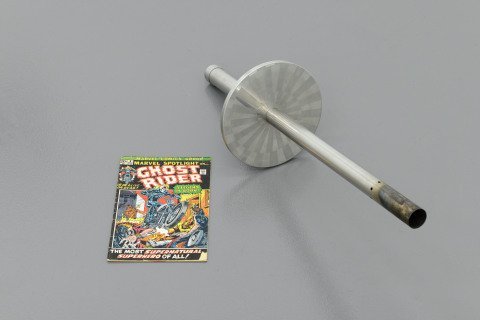

- Nick Darmstaedter, Commuting All Death Sentences to Life in Prison, 2014, 1972 Olympic torch and Ghost Rider comic book.

- Nick Darmstaedter, I Could Dance Forever! Oh, My Hemorrhoid, 2014, Italian marble, 72 salted sweet cream butter stick wrappers, dimensions variable.

- Nick Darmstaedter, T2MamaTambien, installation view, T293, Rome.

- Nick Darmstaedter Squeal Like A Pig!, 2014 UV curable ink on concrete, 48 x 36 inches. Detail.

- Nick Darmstaedter Squeal Like A Pig!, 2014 UV curable ink on concrete, 48 x 36 inches. Detail.

- Nick Darmstaedter, T2MamaTambien, installation view, T293, Rome.

- Nick Darmstaedter at the opening of The Still House current show at the Dhondt-Dhaenens museum in Deurle, Belgium.

The new body of works presented by Nick Darmstaedter at T293 in Rome for of his first solo show in Italy (T2Mama Tambien, until 31 January), stems from two specific focal points: the idea of masculinity and a particular frame of time in the Seventies, the leap year 1972, that the very accurate exhibition’s introductory text – a sort of useful guide to the extended system of cultural references/elements enacted by the artist – reports was the longest year in history, according to the Coordinated Universal Time (UTC). To better understand how Darmstaedter’s visual manipulation of this cluster of information works we reached him on the phone in Rome.

Why did you chose the year 1972?

I don’t remember exactly how I stumbled on it, but I think I heard about a couple of interesting things that happening in 72’ and started building a case. Like two of my childhood idols, Eminem and Dwayne ‘The Rock’ Johnson were born then, which I found weird cause I never thought of them being the same age. I started to research the year in more depth and got really into it. I also found that 1972 really related to this idea that I had been thinking about a lot of what it means to be a man and just the idea of manhood in general. How that standard has changed over time.

The 1970s will likely be considered as the golden decade of the twentieth century, in terms of music, literature and cinema. Anyway one of the common characteristics that you spot in the art production of that time is violence.

It’s true, especially in film. The God Father was the biggest movie of that year which I think set the bar for every violent gangster movie to follow. Then Deliverance was kind of the rummer up which deals with male dominance, and rape. Aguirre Wrath of God and Last Tango in Paris are two other great films from 72’ that are all about male power and dominance. Then you have Pink Flamingos, by John Waters, which kind of puts the idea of manhood way up in the air.

Do you see any particular similarity between the 1970s and the time we are living in?

I don’t feel that the 70s and now are more closely related than any other period.

There are two other key words related to the 1970s that could be useful to take into account. The first one is sharing. Now we share via internet, while in the 1970s sharing was mainly a political concept.

Yeah that’s true, but I didn’t touch very much on any political issues in this exhibition. There is a lot going on. Like Watergate. There’s also this famous picture of Jane Fonda, at that time, showing her in Vietnam sitting on a tank with some North-Vietnamese fellas, as if she was just like hanging out with them having a laugh even though they were killing Americans every day out there. So that picture, or that kind of information published and shared via the newspapers, was extremely powerful. Now I think that it is easier, and an image of the same kind wouldn’t have the same effect on the public opinion. I also have to mention the scandal of the fake Howard Hughes’ autobiograph written in 1972 by Clifford Irving. Hughes was a mysterious character at this point, living out of public life, and Irving was convinced that he wouldn’t come out of hiding to denounce the book. But the author was ultimately condemned. The book never came out in the United States, but you can get a copy of it if you order from the UK.

The second key word is crisis.

There was an episode, again occurring in 1972, called the Pierre Hotel robbery. It happened in New York City the first day of 1972 when everybody was sleeping their new years hangover off, and became the largest and most successful hotel robbery in history. A Uruguayan airplane crashed in the Andes with 45 passengers. The survivors had no food and no source of heat in the harsh conditions at over 3,600 meters altitude. Faced with starvation the survivors fed on the dead passengers who had been preserved in the snow. It was stuff like this that got me really excited about the year.

In the realm of the visual arts, at that time, one of the main emerging movements was the Arte Povera, which the Still House Group seems to share some basic elements with, like the use of everyday, sometimes poor materials, with a non-representative approach.

I think that what we do is similar and people can relate it to certain other movements as well, but I don’t think the Still House thing is necessarily a movement. We are all separate artists who just started showing together out of necessity, and working together out of necessity. Since then it’s been growing and changing so much every year that I don’t really know what to call it.

Would you consider yours a object-based or a information-based art practice?

When I make a work of art there is a lot of information in my mind, but it’s not extremely important to me that other people know about this information in order to enjoy the art. I am a visual person, I make things intentionally to look good, but if someone is interested and wants to know more about what they’re looking at, there is information for them.

Does it take you longer to make the physical painting, or to research about the information related to it?

I do more researching. Before I start a body of work and during the time that i’m making it. Generally my paintings don’t require that much craft, or even skill, I would say. I can train anybody to make much of work that I make and it would look the same. This kind of work gives me time to sit and think about what i am doing and why I am doing it, if i dont like what i’m doing then i stop doing it. If i find that exploring further into the work gets more interesting as time passes then i keep working on it.

Would you consider your art practice a conceptual one?

I like to explore a certain idea and then move to another one. Most of the works that I make do stem from a certain concept, but “conceptual” makes me think of a different kind of art.

Four of your new works consist of images printed on concrete that, in a certain way, seem to dialogue directly with antique detached frescos which Rome is rich of. After Wade Guyton, many artists are exploring the many possibilities of printed images and photography. The first one that comes to mind is Peter Sutherland, who was in residence at the Still House. Do you intend to explore this same field?

There are a lot of people printing on different kinds of materials. I had images I wanted to display and was looking for a material that went well with the idea of the show and thought that concrete was a good option. I’d never seen a print on concrete before so I did it.

Do you think that this idea of producing works by starting from a certain year, 1972 in this case, would be as much stimulating if choosing a different century? Let’s say 1472, for instance?

I think so. If you research any year I’m sure that you would find a lot of fascinating stuff. It’s a pretty vague concept to delve into a year, but I felt that this particular one was special and somehow connected to me in particular.

After having worked a lot on masculinity in 1972, what do you think about today’s masculinity?

As technology, business, and style evolve, masculinity becomes more and more subjective.

December 19, 2014