Rodrigo Hernández at Pivô: the abstract nun looks sensual

Rodrigo Hernández solo presentation at Pivô melts dreamed dreams with reality and turns abstraction into a personal map of Modernism.

The practice of Mexican-born artist Rodrigo Hernández is grounded on various historical references and anecdotes. Take for instance his 2017 solo show at Berlin’s Chert Lüdde gallery, titled J’aime Eva (I Love Eva, in free translation), which placed a collage that Pablo Picasso produced during the summer of 1912 – allegedly the sole one he made that season – as its starting point. Guitar: J’aime Eva was the Spaniard’s homage to his then lover Marcelle Humbert (aka Eva); by its turn, the work is said to’ve been somehow inspired by a painting authored by Henri Rousseau – the Douanier who once famously told Picasso: ‘you and I are the two most important artists of the age – you in the Egyptian style, and I in the modern one’. Within Rodrigo Hernández vocabulary, these events were translated into eight works, all bearing Eva in its titles, spanning techniques such as collage, drawing and painting. The process to create The Real World Does Not Take Flight, his current exhibition at Pivô, in Sao Paulo, follows the same modus operandi.

- Rodrigo Hernández, We, too, can divide ourselves, 2018. Cardboard, papier-mâché, acrylic paint, oil paint, 47 x 43 x 9 cm. Courtesy Pivô, Sao Paulo. Photo: Everton Ballardin

- Rodrigo Hernández, We, too, can divide ourselves, 2018. Cardboard, papier-mâché, acrylic paint, oil paint, 47 x 43 x 9 cm. Courtesy Pivô, Sao Paulo. Photo: Everton Ballardin

- Rodrigo Hernández, Alive, 2018. Cardboard, papier-mâché, acrylic paint, oil paint, 56 x 18 x 21,5 cm. Courtesy Pivô, Sao Paulo. Photo: Everton Ballardin

- Rodrigo Hernández, Alive (detail), 2018. Cardboard, papier-mâché, acrylic paint, oil paint, 56 x 18 x 21,5 cm. Courtesy Pivô, Sao Paulo. Photo: Everton Ballardin

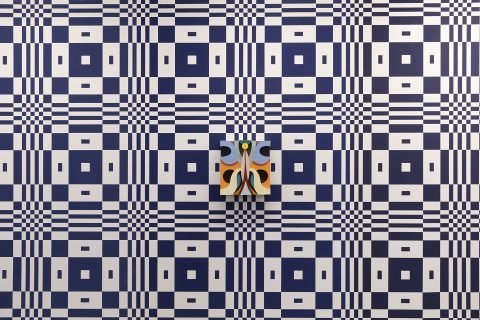

- Rodrigo Hernández, These cells, 2018. Cardboard, papier-mâché, acrylic paint, oil paint, variable dimensions. Courtesy Pivô, Sao Paulo. Photo: Everton Ballardin

- Rodrigo Hernández, These cells (detail), 2018. Cardboard, papier-mâché, acrylic paint, oil paint, variable dimensions. Courtesy Pivô, Sao Paulo. Photo: Everton Ballardin

- Rodrigo Hernández,The Real World Does Not Take Flight, 2018. Installation View. Courtesy Pivô, Sao Paulo. Photo: Everton Ballardin

- Rodrigo Hernández,The Real World Does Not Take Flight, 2018. Installation View. Courtesy Pivô, Sao Paulo. Photo: Everton Ballardin

- Rodrigo Hernández,The Real World Does Not Take Flight, 2018. Installation View. Courtesy Pivô, Sao Paulo. Photo: Everton Ballardin

The show steams from a two-months residency that the artist partook at the institution, and is informed by the realm of dreams. In fact, by a particular dream that Rodrigo Hernández dreamed twice within a week interval; the first time it stroke him as mundane, but on the second such coincidence was taken as symbolic – noteworthy, the artist had recently lost his mother. The dream’s narrative was set in London, a city that Rodrigo Hernández had visited twice, and pictured a man following a nun from Bloomsbury to the Victoria & Albert Museum, in Kensington. Such specificity of details is suddenly blurred by the very voids that characterise the subconscious layers of perception, and through a series of unclear events, eventually both characters talk to each other. The nun presents herself as Mo-Po, a sister who is dedicated to help youngsters to perform sex surgeries. The narrative continues in a fragmented manner, in a hospital, then again inside the museum, then on the streets and so forth. Adding to the bowl, an obituary of the nun accompanies the press-release, dragging her from the dream to the real world.

The Real World Does Not Take Flight – a title borrowing the opening line from Wislawa Szymborska’ poem The Real World – consists of a site-specific installation occupying Pivô’s second-floor. It beautifully plays with notions of background, foreground and mid-ground, that is, the operation par excellence of collage, thus attesting to the artist fondness and mastery of such technique. In a quasi-wallpaper-like gesture, Rodrigo Hernández covered all the space’s walls with a same geometric pattern (Field of Flowers), made of white and dark blue rectangles. On top of it are eight three-dimensional wall works, all from 2018, at times colourful and geometrical (such as We, Too, Can Divide Ourselves), at times more inclined towards figuration (as in Alive or These Cells). We learn that the wallpaper-ish piece is based on the patterns of the Scott Paper Company Dress, from the 1960s, which supposedly can be found in exhibition at the V&A. Having said so, as it often occurs within Conceptual art, the oneiric trope of nuns ends up detaching itself from the aesthetics of the show, which appears to be an harmonious and powerful presentation. It is certainly strong enough to hold the tales that engendered it expanding the spectator’s vision. Rodrigo Hernández use of Pivô’ space – a notoriously tricky one, marked by Niemeyer sensual curves – is delightful. Perhaps you may argue that the discourses surrounding the show challenge, at some point, its moving aesthetic beauty. This may be the case when, as it is said, it’s better for a cigar to be just a cigar.

September 18, 2020