Jan Domicz meets Jean Prouvé

For our ‘at the show with the artist’ section we sat down with Jan Domicz to question him about his relationship with metal worker and architect Jean Prouvé.

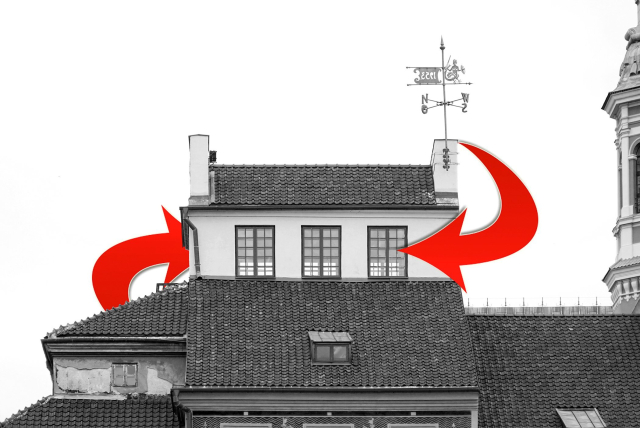

Traditional lantern in Warsaw, Poland. Courtesy of Jan Domicz.

Jan Domicz’s artwork revolves around the misplacement of objects and architectural elements for the sake of creating new meaning for them. Although such practice of misplacement has become somewhat of a signature gesture in much of last century’s contemporary art, we find a fruitful originality in Domicz’s action of fabricating and designing these objects and architectural elements himself, as opposed to simply appropriating them. Moreover, his attention for an aesthetically charged installation of these elements broadens the scope of what would otherwise be a mere misplacement.

For this “At the Show with the Artist”, we decided to comment on Jean Prouvé’s shutters, which are elements of one of the French architect’s buildings in French-colonised Guinea. These large aluminium panels, originally designed to reflect the sunlight hitting the facade, have now been removed and are sold as collectable artworks, like many other architectural elements made in Prouvé’s manufactures. These shutters have acted as a stimulus to talk with Domicz about his own practice.

Jean Prouvé, Sun shutter, 1957, Aluminum. Courtesy of Galerie Jousse Entreprise.

Let’s start this conversation with your piece Lamps on a Lamp Shop, for which you placed some lamps on the roof of a lamp store building during closing hours. In the caption you write that the piece is a way to transform consumer goods—lamps—into a commercial of themselves, which reads as a critical motivation from your part. At the same time, there is something simply funny and absurd in the image of these lamps on top of the building. Were you more interested in the serious or ironic aspect of the piece?

Jan Domicz, Lamps on a lamp shop, installation shot, 2015. Courtesy of the artist.

JD: Serious and absurd at the same time. Those two qualities need each other. In the process I consider humour as a conscious side effect or “production bonus” to use film industry term. I was struck by how seriously my sketch for the Lamps on a lamp shop was taken by the shop’s manager and owner. They knew that the piece would look like shops promotional activity in the moment of refusal/decline/moving out. After the piece was done, I gave them half of the flyers I produced using photo documentation of the work, which they then used as their promotion in the shop. The other half of the flyers was shown during my exhibition in MMK Frankfurt/Main.

In the case of Prouvé’s shutters, do you see some irony and absurdity in an indoor display of an architectural piece designed to block the light from outside, or rather it is its conceptual charge that strikes you the most about them?

UAT building, Conakry, Guinea. Courtesy of Galerie Jousse Entreprise.

JD: Prouvé’s shutter and his practice in general operate now in a similar doubling fashion. As functional architectural elements, and as collectable art object. The art market is very good at fetishizing anything. Shutters are fascinating for the way they stand alone, without a building. Their removal from the realms of functionality or context makes them very exciting. Prouvé would have never arrived at the same conclusion with his manufactures and production of serialised architectural elements. The move from one mode to the other makes us talk about them now. Conceptual charge pins it down. Adds to the aura.

As someone interested in misplacing objects to give them new meaning, how do you see this appropriation of a functional object—the shutters—for the sake of making it into an artwork? As you say, it is unlikely that Prouvé intended his architectural element as a sculpture, and yet it has now become one.

JD: Things (or culture in general) are around to be used. Let’s appropriate a quote from It’s Hard to Find a Good Lamp by Donald Judd: “The intent of art is different from that of the latter [furniture], which must be functional. If a chair or a building is not functional, if it appears to be only art, it is ridiculous. The art of a chair is not its resemblance to art, but is partly its reasonableness, usefulness and scale as a chair.”

The fundamental and only difference between art and not-art are intentions. Prouvé’s shutter from his perspective will never be art. They will be shutters stolen from a building and sold on art market. However, I have no problem with works changing their operational mode. Art can also be used outside its original environment. One can change usefulness back and forth but cannot change the intent.

In your piece BnB, you started from the iconic lantern found on the roofs of historical buildings in Warsaw to build a similar structure on the roof of an art gallery. From an aesthetic point of view, there is something visually powerful to it, as it imitates the original lanterns while creating an entirely new shape, a rather stripped-down version of the original. How did you go about designing your lantern? Were highly aesthetic architectural elements such as Prouvé’s shutters of inspiration for you in this process? If so, which ones and why?

Jan Domicz, BnB, installation shot, 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

JD: The making of this piece was highly structured. The first decision was to use the shape of the lanterns from Warsaw old town. I went through number of archival plans to find the most simplified version which could fit the size of the gallery’s rooftop. The second decision was to pick the material. Expanded Aluminium net and profiles. To answer your question directly: yes, the aesthetics of architectural elements was useful, especially generic ventilation and air conditioning units, the ones you can find on a rooftop of almost any office building. Only less lazy architects are trying to hide them. Typically, these installations are added without integrating them into the appearance of a building. Historical lanterns in Warsaw look like semi-detached houses added on top of tenement houses.

It’s funny you call the process designing. In this case designing means: to find/ to copypaste/ to reduce/ to change the material/ to place in a new context.

Your Parrot Stands are replicas of a tram seat that you fabricated to be as close to the real object as possible. Apart from the practical reason of not being able to physically appropriate the seat, were there other reasons as to why you preferred to design it yourself instead of showing the original in a gallery context? Interesting in this regard is to note that Prouvé’s shutters are found objects that retain a strong aura of authenticity, while we could speculate that if you displayed the real seats as found objects, they would feel less authentic than your own fabricated version of them.

Jan Domicz, BnB, installation shot, 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

JD: I fully agree. The copy gets more real as retelling a story makes it more authentic and embedded. Making a new copy is needed for the work to function. Without an original seat/stand in the urban context, my version in the gallery would not work. Their purpose differs from the one of the original. Moreover, a vital part of “Stands” series is the fact that they are not attached to the floor. They are easy to install in the exhibition but useless while considering the initial purpose. One cannot lean on the art piece. It goes back to the statement that the intention behind an artwork is different from that behind a piece of furniture.

The aura of authenticity is important for those selling and buying Prouvé’s shutters. Although this process looks like my practice, I am not going for authenticity. For me the work is made in the act of moving a certain shape from one context to the other–misplacement or a moment of being “out of space”.

Having that in mind I would like to end with an outtake from a new narrative piece I am currently working on.

With each reproduction, he finds himself further removed from the original. As more perfect, celebratory (beautiful?) versions are created, the original meaning recedes further and further. His only option is to keep working.

January 29, 2019