Simone Peterzano: master of Caravaggio and censorship’s survivor

Simone Peterzano was a pupil of Tiziano, and the master of Caravaggio. But he had to compromise with the Church. Discover all his public works.

Even for art historians that of Simone Peterzano (Venice 1535 circa – Milan 1599) has merely been a name for a very long time. None has ever really been interested in this late Mannerist painter who signed more than one work titiani alumnus “student of Titian”. On the contrary, hardly anyone believed in this apprenticeship . That seemed to be just boasting, simply showing off an exclusive curriculum so to impress the clients. Then, all of a sudden, attention was given to Peterzano. It was 1927, when a young art historian from Germany, Nikolaus Pevsner, discovered a contract from 1584 by which Peterzano committed to hosting a 13-year-old boy, to providing him with board and lodging, and assuring that by the end of the apprenticeship – that was going to last four years – the apprentice would learn all the skills he needed to paint on his own. The contract was signed by Peterzano and the boy himself; his name was Michelangelo Merisi.

The discovery is deflagrating. The art world finds out that Peterzano, overlooked for almost three centuries, has been the master of one of the most revolutionary painters between 1500 and 1600: Caravaggio. Many scholars start to show interest for the unknown artist; and that’s how his luck within art criticism begins.

Studies have recently led to new discoveries which are well presented in the first ever exhibition dedicated to Peterzano in Italy, help at the Accademia Carrara in Bergamo: Titian and Caravaggio in Peterzano (in the Gamec’s rooms until 17 May 2020, curated by Simone Facchinetti, Francesco Frangi, Paolo Plebani and Maria Cristina Rodeschini). The exhibition suggests new evidences that back up a possible Venetian origin of the painter (while some biographies still report Bergamo as his place of birth). It also offers further evidences in favour of his apprenticeship with Titian which has long been questioned.

Today many of his works are part of important public and private collections, amongst which the Maurizio Calvesi collection in Rome; the Galleria di Palazzo Pitti and the Olivetti Rason collection in Florence; the Musée Jeanne d’Aboville in La Fére and the Galerie Canesso in Paris; the Staatliches Museum in Schwerin; the Statens Museum for Kunst in Copenhagen; the Pinacoteca di Brera and the Civico Gabinetto dei Disegni of Castello Sforzesco in Milan. But there are also several works that Simone Peterzano created in public places which can still be seen today in an excellent state of conservation. Here they are on a Milanese itinerary, with a few detours to Monza, Pavia and Como.

From Venice to Milan

There is evidence of Simone Peterzano in Milan starting from 1572. The following year the artist paints two big canvases for the Church of Ss. Paolo e Barnaba. These early paintings are characterised by bright colours that well imply his Venetian education. However, according to the art criticism, Simone Peterzano was deeply influenced, more than by Titian, by two other great painters from Venice: Tintoretto and, above all, Paolo Veronese.

To the realm of naturalism Peterzano adds the sophisticated touch of Venetian ‘colourism’. The Lombard school has just begun to influence his style. At this point, however, the painter has already left the Lagoon behind, at least as far as the decision to move to Lombardy is concerned. It is attested that Peterzano settles down in Milan at Porta Orientale, near San Babila, in 1575. The move from Venice to Milan also coincides with the beginning of a series of important commissions to decorate many sacred places of the city that will keep him busy throughout his career.

Peterzano at the Certosa di Garegnano

In 1578 Simone Peterzano takes part to the large project of decoration of the Milan Charterhouse of Garegnano (Santa Maria Assunta in Certosa, in via Garegnano 28, Milan). Here he frescoes the presbytery, the apse and the dome; this pictorial endeavour will be his most significant public work, what up to now is considered to be one of the pinnacles of his art.

In the apsidal conch he paints a crucifixion that is a tripartite composition where the Virgin and Saint John are singled out by architectural elements while Mary Magdalene is at the foot of the cross. Placed in the apsal area, just below the frescoes, a series of canvases by Peterzano represent passages from the New Testament. That is, the Resurrection, the Virgin enthroned surrounded by Saints Bruno, John the Baptist, Jerome and Ambrose, and the Ascension of Jesus.

Eight angels holding the symbols of the Passion are painted on the dome. Also here – like in the Crucifixion – the composition is created through architectural elements. Each figure has its own space, and is separated from the others by golden stuccoes that mark the octagonal structure, while the Eternal Father, depicted as a bearded figure, is placed at the centre.

There is something Michelangelesque in the twisting of the bodies that instils movement into the figures, in their gestures, and in the strong chiaroscuro; this comes back in the Prophets and Sibyls in the dome cladding and in the Evangelists on the side arches: these latter are majestic figures that stand out against a warm blue background, and are painted with such a strength and warmth that will not be found anymore in Peterzano’s later works in Milan.

Works at the Certosa last until 1582. They give rise to a cycle that shows a perfect balance between the bright colours coming from Simone Peterzano’s Venetian education and that dignity typical of Mannerism, but without being too extreme. At the same time, the master is also able to accomodate the need of propriety and severity imposed by the precepts of Saint Carlo Borromeo.

In 1582 the Counter-Reformation is taking place throughout Europe. Simone Peterzano is thus aware that he must keep the erotic outbursts and the profane languor of his youthful Venus at bay so as not to run the risk of censorship. That is not merely a precautionary measure imposed by the spirit of the times.There is indeed a written agreement, that the painter signs on 31st of October 1578 with Gabriele de Collis, the Carthusian monk who commissioned the cycled. The contract – among other things – requires not only to avoid any hint of eros, but also not to show any bare flesh that could lead to distractions from the faith. Each figure, according to the agreement, will have to be marked by an extreme demeanour, in order to obtain an overall effect of unexceptionable solemnity.

Che tutte le figure humane et massime de santi e sante siano fatte con somma honestà et gravità et non ne apaiano petti ne altre membra o parti del corpo non honeste et ogni atto, giesto, garbo, movenza et drappi dei santi siano honestissimi, pudicissimi et pieni d’ogni divina gravità et maestà.

The clause, of course, follows the precepts of Carlo Borromeo’s Instructiones Fabricae et Supellectilis ecclesiasticae, i.e. the instructions for the decoration of sacred places that the Archbishop of Milan had issued the previous year. A group of experts would express their views on possible “errors of art”, while it would be up to the Reverend Father Prior to report “any error regarding devotion”.

Fortunately for Simone Peterzano, the “pool of experts” (composed by the architect Vincenzo Seregni and the painters Aurelio Luini and Giovanni Battista Ferrari) would then declare that almost nothing in those paintings had to be corrected. Peterzano skilfully succeeds in uniting all the parts. Whilst being consistent with his interest in movement and sinuosity, he nonetheless manages to meet the rigid devotional requirements of the Counter-Reformation.

But the same success won’t be so easily achieved in other sacred places. The tightening up ecclesiastical inspectors. or probably Peterzano giving up on complying with the Counter-Reformation’s spirit, introduce changes that will characterise his style after the 1580s up to his last works.

The Church of Santi Paolo e Barnaba

It is in the early Milanese years (1573) when Simone Peterzano works for the Church of Santi Paolo and Barnaba (Via della Commenda 1, Milan), one of his most demanding commissions in the city. Here he produces two large oil paintings (350 x 415 cm): The Vocation of Saints Paul and Barnabas and Saints Paul and Barnabas at Lystra. In these works Simone Peterzano’s painting deeply differs from the school of Lombard painting. But his style can certainly not be dismissed with a simple reference to the Venetian school. As Simone Facchinetti puts it, “In the Vocation of Saints Paul and Barnabas there is a figure in the foreground, seen from behind, showing incipient baldness. If singled out from the rest of the painting it seems to be in front of an ante litteram passage from Caravaggio. It is an example of the extraordinary tension towards that naturalism which will enliven Simone Peterzano, at least up to the construction site of the Certosa di Garegnano”.

However, unlike the works for the Certosa di Garegano, which manage to please Carlo Borromeo’s demanding inspectors, these canvases have to deal with censorship. Seven years after they are made and placed inside the church, in 1580, they end up being noted by the ecclesiastical authorities, who order all the “indecorous and improper” aspects to be corrected. Simone Peterzano is then called back to work so that within a month he would cover the “improper nudity” and repaint the portraits of the people who are still alive so that they cannot be recognised.

Siano coperte le indecenti nudità di quelle immagini che sono sopra li quadroni in chiesa; raconciando ancora le imagini de viventi in tal modo che non rappresentino più quelli.

Thus, for example, in The Miracle of Saints Paul and Barnabas at Lystra, a puffball drapery is added to the female figure who is bending forward with a bundle of sticks to cover the “indecent” naked shoulder. To the character, certainly a portrait of a contemporary gentleman, who appears behind the Priest of Zeus is added an incongruous turban in order to make him unrecognisable. The other figures are also retouched by Simone Peterzano, except for one: the still rather young man who is dressed according to the fashion of the time, wearing a hat and a black robe, with a flashy white gorget. He seems to be staring at those who are looking at the painting. It is quite likely that this is Simone Peterzano’s face, and that the painter – bursting with pride and rebellion – refused to delete at least his own self-portrait.

Beyond these aspects, the two large canvases of 1573, as Francesco Frangi notes, ” are perhaps the most spectacular achievement of Milanese painting of the time. The recently completed restoration has shown an extraordinary quality of execution, able to contaminating the colorism of the Venetians with real-life studies of the luminism, typical of the Lombard figurative tradition”.

The church of San Maurizio al Monastero Maggiore

Slightly prior to the two teleri for the church of Saint Paolo and Barnaba, are the frescoes in San Maurizio al Monastero Maggiore (Corso Magenta 15). According to documents, they can be dated precisely to 1572-1573: we are therefore facing Peterzano’s first public commission in Milan. Here, the painter decorates the interior facade with two scenes surmounted by their respective lunettes on the counter-facade at the sides of the entrance. These are two frescoes depicting the Return of the Prodigal Son and the Expulsion of the Merchants from the Temple. The latter, in particular, represent an ideal subject to create a theatrical and emphatic representation, which can once again bring out Peterzano’s sensibility for movement typical of Late Mannerism. This can be seen above all in the act of Jesus who, perhaps for the first and only time in the New Testament, energetically reacts by entering the Temple and finding the merchants there. As Simone Facchinetti points out.

The painter presented himself at the appointment with the best intentions, creating one of his most memorable works. In the narrative scenes there is a clear and magniloquent rhetoric of gestures. Christ who drives the merchants out of the Temple, with his violent reaction, unleashes an unstoppable movement of things, animals and people. There are those who tumble to the ground, those who flee with their herds and those who secure their money. Also in the Return of the prodigal son the two main actors are the engine of the story, they animate it with their emphatic embrace and set off an emotional wave of chain reactions. They are both episodes of great scenic impact where everything is in fibrillating movement.

The church of San Maurizio al Monastero Maggiore is a wonderful decorative project that contains remarkable works by other leading masters of 16th century in Milan. These include the cycles signed by Bernardino Luini and his sons placed respectively on the partition walls of the nave and in the side chapels. All the frescoes, including those by Simone Peterzano, have been the subject of a recent restoration that has placed back the church among the most evocative stops on a journey through Renaissance and Mannerist art in Milan.

Other works by Peterzano between Milano, Monza, Pavia and Como

Simone Peterzano would have made several other works on canvas for sacred places in Milan, many of which are still in their original location. Among the others, those in the church of Santa Maria della Passione in Milan (Via Vincenzo Bellini, 2) are similar, as far as style is concerned, to the works of Antonio Campi, in particular the Assumption of the Virgin (1587) in the sixth chapel. In the same church are also preserved the canvas with the Madonna with Child and Saints and the one with the Annunciation.

The interventions in the Church of Sant’Angelo in Milan (Piazza Sant’Angelo, 2) can be dated more or less to the same period: a cycle of frescoes in the eighth chapel on the right, with the Eternal Father in glory among the angels in the vault and with the Miracle of the Mule and the Preaching of St. Anthony on the walls. In the same church, but today kept in the sacristy, is the canvas of the Holy Family with the mystical wedding of St. Catherine (datable around 1579).

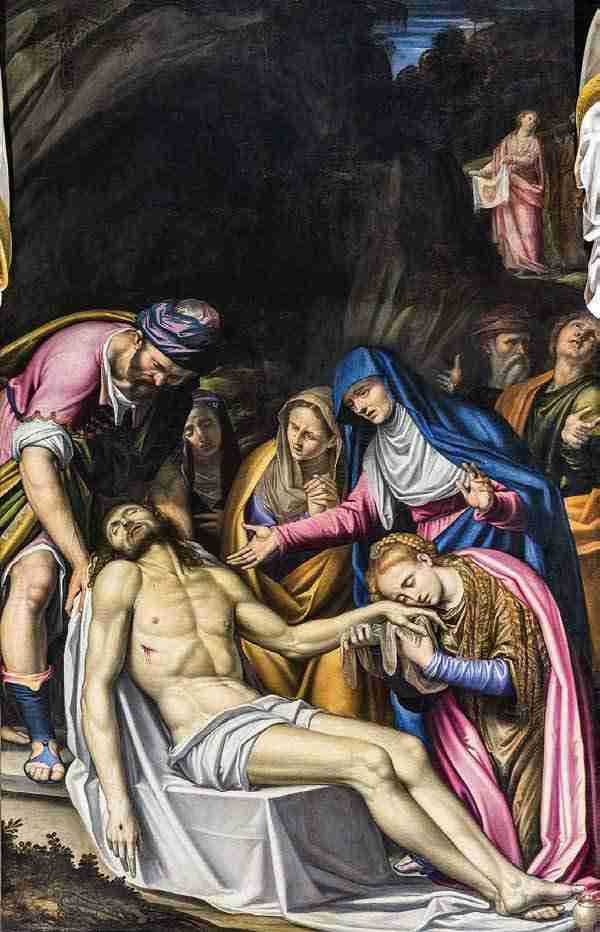

For the church of San Paolo Converso (in Piazza Sant’Eufemia 1 in Milan, here is a link to our writing about it) Peterzano had painted a canvas representing The Pentecost, now in the nearby Basilica of Sant’Eufemia. For the destroyed church of Santa Maria della Scala he had instead painted the Pietà (or Deposition from the Cross) now preserved in San Fedele (Piazza San Fedele 4 in Milan). In this painting, as Maurizio Calvesi noted, it is worth paying attention to the theme of light:

Already strong in San Barnaba, [the light] here becomes violent. It widens into the detached figure of Christ, in a uniform manner, without contractions, but contributing with its corrosive quality to making the body poignant; instead it suddenly hits, with abrupt interruptions, the face of Christ himself, the faces and clothes of the pious women; it cuts the curved shoulder of Joseph of Arimathea, it vanishes his left arm into a sparkling spot that smear the dark margins of Christ’s hair; it burns, following a filiform course, the wide curve of the Magdalene’s mantle. The colour (this time markedly reminding of Veronese), sumptuous and pleasant, of undeniable mastery, is called upon to perform its usual decorative function, in clear denial of any authentic dramatic concentration.

The late years of the painter’s life take us just outside Milan, to Pavia for instance. In the Church of Santa Maria di Canepanova (via Defendente Sacchi 15), the altarpiece of the right chapel is by Simone Peterzano: a Nativity with Saint Anthony of Padua. To Monza, where in the Church of Carrobiolo (Piazza Carrobiolo), there is the altarpiece with the Holy Family with St. Giovannino, St. Elizabeth and Saints Peter and Paul, while another altarpiece with the Glory of All Saints, originally in the church, is now preserved in the nearby convent. To Como, where a work by Peterzano is in the Church of Sant’Agostino (Piazza Giovanni Amendola, 22): an altarpiece with a Madonna and Child with Saints.

Peterzano’s style in these works has changed since his debut in Milan. In the Certosa di Garegnano (where the frescoes were completed in 1582), the figures still appeared toned, the muscles are clearly visible. But after the 1580s his style changes. The colours become colder, the palette less rich, and even the shapes gradually change to become simpler and simpler. From the mid-80s, the bodies begin to lose presence and physical structure; in some cases almost fading away. In the second part of his Milanese period Peterzano would no longer be the foreigner who brought Titian’s echoes to Lombardy: the Counter-Reformation would penetrate his brush, significantly determining his coloristic and formal approach.

In the last years of his career, Peterzano has also painted an important altarpiece with Saint Ambrose between Saints Gervasius and Protasius (1592) for the altar of Saint Ambrose in the Duomo of Milan, a work that is now preserved in the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana. Finally, we know that on 25th and 30th June 1596 he received payments for an Annunciation, a work that has long been erroneously identified with a contemporary canvas of similar subject by the painter kept in the Oratory of San Matteo della Banchetta in Milan. Unfortunately, since San Matteo della Banchetta is a private church, it is not accessible to the public. And that physical limit, which forces us to stop on the churchyard, also marks the temporal boundary of what we know about Simone Peterzano: after the realization of that work all trace of him is lost until the act of death dating back to 1599. Exactly the year in which his pupil Caravaggio, in Rome, receives his first public commission: the spectacular paintings of the Contarelli chapel in San Luigi dei Francesi.

Bibliography

- La Certosa di Garegnano, di M. Colli, R. Gariboldi, A. Manzoni, editore Biblioteche Pubbliche Milano, 1989.

- Aggiunte a Simone Peterzano, di C. Baroni, in L’Arte, n.IV; XLIII, 1940, pp.173-188.

- Simone Peterzano. Maestro del Caravaggio, di M. Calvesi, in Bollettino d’Arte, s. 4, XXXIX (1954), pp. 114-133.

- Simone Peterzano, di A. Morassi, in Bollettino dell’Arte, XXVIII (1934).

- Peterzano. Allievo di Tiziano, maestro di Caravaggio (catalogo della mostra a Bergamo, Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, 6 febbraio – 17 maggio 2020, a cura di S. Facchinetti, F. Frangi, P. Plebani, M. C. Rodeschini), Skira, Milano, 2020.

- La pittura in Italia – Il Cinquecento, AA. VV., a cura di G. Briganti, Electa, Milano, 1988. Gli affreschi della Certosa di Garegnano, a cura di M. Gregori, Amilcare Pizzi, Milano, 1973.

November 25, 2020