Honoré de Balzac’s Frenhofer and his Unknown Masterpiece

Artist Frenhofer, protagonist of The Unknown Masterpiece by Balzac, never fails to raise questions. Especially if you ‘reverse’ him.

After almost two centuries since its first publication in 1831, The Unknown Masterpiece by Honoré de Balzac is still very relevant for the questions about art one can find in it. The short story and its brilliant main character, Maître Frenhofer, deal with the essence of art, with the struggle between poetic intention and aesthetic results, and the relationship between the artist and the public. Beside providing new insights into these important topics, Balzac’s story has inaugurated an entire debate about the relationship between literature and visual art.

[On the topic of the relationship between literature and visual art, this is our list of art novels. Ed.]

In his tale of a quest for an (impossible?) absolute masterpiece, Balzac takes us to Paris on rue des Grands-Augustinis in the early 17th century. Two painters meet one of the greatest masters of their time, a fictional character named Frenhofer. He preaches about the perfection of painting, giving practical examples of his mastery and delving into the theoretical difference between truth and appearance. Frenhofer immediately frames himself as the only custodian of an unsurpassed technique, the one capable of transferring “the breath of life” to canvas. The famous master also reveals a secret to the two painters. For ten years he has been working on the portrait of a woman, Catherine Lescault, which should become the most perfect artwork ever seen. That work, says Frenhofer, should allow people to see how he was able to take painting to a dimension no one had ever reached before: the equivalence of art and life.

[In regards to the still pivotal equivalence, see our interviews with contemporary painters Lucy Stein and Louis Fratino. Ed.]

Three months after that meeting, Frenhofer announces that his picture is finished. However, when he shows it to the two friends, what they see is disappointing. There is nothing of what the master promised. The two spectators find themselves in front of the sad spectacle of “ confused masses of color and a multitude of fantastical lines that go to make a dead wall of paint.” Only after a closer look, the two friends discover “a bare foot emerging from the chaos of color, half-tints and vague shadows that made up a dim, formless fog, [of] living delicate beauty.” There is indeed a beautifully painted woman under that blanket of colors, but the incessant work of Frenhofer, with the continuous repainting in search of absolute perfection, projected the artist into a solipsistic vortex until he lost all relationship with reality. Faced with the disappointment of his public, Frenhofer falls into the deepest despair, which leads him to the destruction of all his works and eventually to his death.

At first sight, the main theme of the short story is the relationship between representation and reality. The masterpiece is “unknown” because it is unachievable, therefore unknowable and incommunicable. Critics have traditionally pointed to a second theme too, that is the clash between the artist’s intention and the final result. One could even go further and ask with whom to sympathize. Is it the two friends, objective witnesses to a crude reality their teacher is unable to see? Or is it Frenhofer, convinced that he has painted the absolute masterpiece and then erroneously persuaded of the contrary by the two friends? Balzac’s story finds a new topicality in these questions.

The tale confuses different dimensions. For example, it is unclear whether it is the idea (the work of the mind) that canceled the sign (the figure in painting), or if instead it has been the sign (the continuous repainting) that has lost the meaning. (Agamben 1999 [1994]) In both cases, the masterpiece remains unknown to the two friends and its maker. It is precisely in the relationship between these characters that the issues at stake are enriched with a new element. Along with the confrontation between the artist’s intention and the result on the canvas, the opinion of the public emerges as a new question. Philosopher Giorgio Agamben addressed this aspect as follow:

What happens to Frenhofer? So long as no other eye contemplated his masterpiece, he did not doubt his success for one moment; but one look at the canvas through the eyes of his two spectators is enough for him to appropriate Porbus’s and Poussin’s opinion: “Nothing! Nothing! And I worked on this for ten years.” Frenhofer becomes double. He moves from the point of view of the artist to that of the spectator, from the interested promesse de bonheur to disinterested aesthetics. In this transition, the integrity of his work dissolves. For it is not only Frenhofer that becomes double, but his work as well; just as in some combinations of geometric figures, which, if observed for a long time, acquire a different arrangement, from which one cannot return to the previous one except by closing one’s eyes, so his work alternately presents two sides that cannot be put back together into a unity. The side that faces the artist is the living reality in which he reads his promise of happiness; but the other side, which faces the spectator, is an assemblage of lifeless elements that can only mirror itself in the aesthetic judgment’s reflection of it. (Agamben 1999 p.9, [1994])

Agamben concludes:

Aesthetics then not only would be the determination of the work of art starting from the αἴσθησις, from the sensible apprehension of the spectator, but also would include from the beginning an examination of the work of art as the opus of a particular and irreducible operari (working), the artistic operari. (ibid.)

Balzac’s short story not only introduces the themes that would dominate the 20th century up to the “awareness of the impossibility of exactness,” (Bachmann 1993) but also pioneers the reflection on that “change in the essential status of the work of art”(Agamben 1999 [1994]) offered by modern art: a new aesthetic balance between artist and spectator.

[In regards to the idea of art as as the opus of a particular and irreducible (working), we would mention the work of a contemporary artist such as Kristof Kintera. Here is a link the short essay we wrote about him on occasion of his exhibition at Collezione Maramotti in Reggio Emilia. Ed.]

From Mabuse to Cézanne

The Unknown Masterpiece is set in the early 17th century. Frenhofer declares himself a direct pupil of Mabuse, a moniker for the Flemish painter Jan Gossaert (1478-1532). The two friends, witnesses of his failure, bear the names of two real painters: Poussin (Nicolas Poussin, 1594 – 1665) and Pourbus (Frans Pourbus the Younger, 1569 – 1622). At the time, the memory of artists like Raphael and Titian, mentioned by Frenhofer as absolute models, is still vivid. In a few short passages, Balzac contextualises those artists within a critical discourse. His story points to different eras where the categories of beauty, verisimilitude and mimesis were disappearing, where questions about the relationship between artwork and thought were coming to the fore, becoming more and more central in relation to the technical limits of painting.

In The Madonna of the Future from 1837, Henry James proposes an even more extreme version of the Balzachian story, with renunciation as the only possible outcome of the quest for the perfect masterpiece. The absolute idea can only live in the mind of the artist, and it is doomed to disappear when it takes the form of a work of art. Balzac’s story also influenced several artists. For example the painter Émile Bernard recalls in his Souvenirs that Paul Cézanne was literally struck by The Unknown Masterpiece.

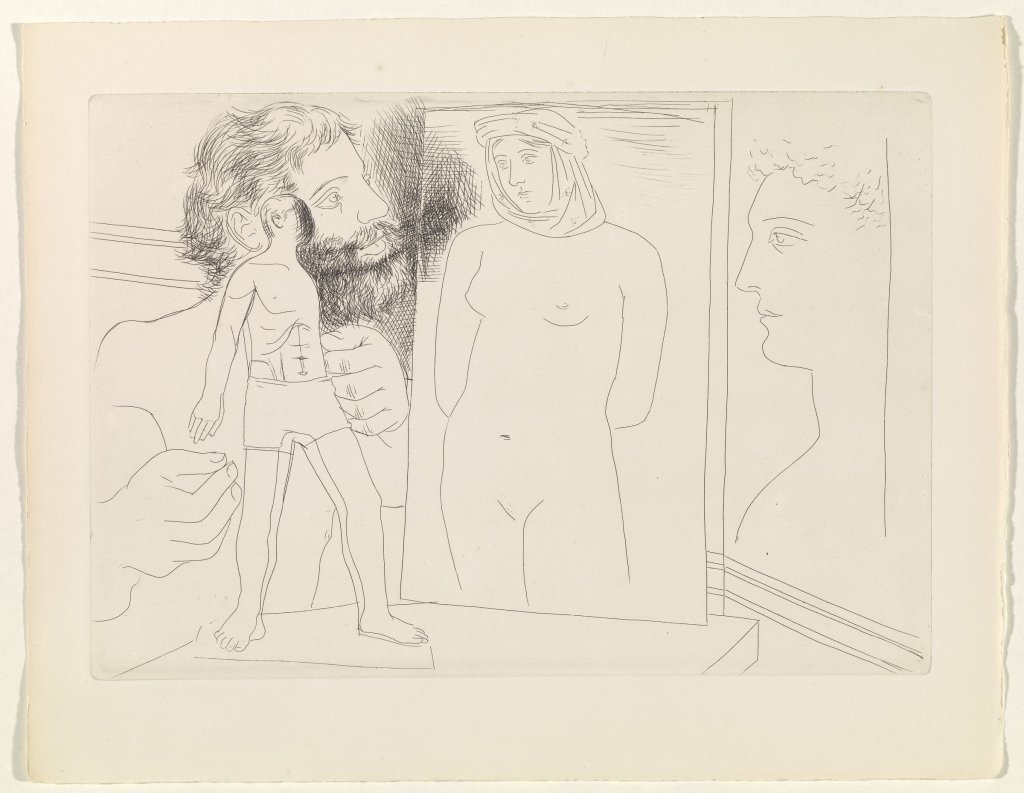

An edition with Picasso

The Unknown Masterpiece (Le Chef-d’oeuvre Inconnu) was first published in 1831, and an extended version came out six years later. Its definitive edition was finally released in 1847, although a note by the author mentions 1845. Almost a century after Balzac’s death, the story was republished as a precious limited edition (350 copies) with a series of illustrations by Picasso (here is a link to the copy in the collection of the MoMA in New York. The book is also available at the Gagosian gallery shop). Responsible for this publication is the famous art dealer Ambroise Vollard, to whom artists such as Cézanne, Rouault, Gauguin, and Van Gogh owed their fame. By combining Balzac and Picasso, the dealer and publisher managed to produce a book where literature and art coexisted freely, avoiding didacticism in the references between text and images.

The illustrations by the Spanish artist include 12 original etchings, 20 drawings, and 67 woodcuts. Some of them are made of only points and lines, working as an introduction to the sections. Others are spread across the text, without however having any direct narrative connection with it. The 12 original etchings outside the text were made specifically for this publication and they link to Balzac’s story only thematically, delving into the relationship between the painter and his model.

Vollard had been courting Picasso for this edition of The Unknown Masterpiece since 1926, although it is not clear whether Piacasso was familiar with the short story. In the end, Vollard managed to bring two incomparable authors together in a single volume through the topic of the “creator-creature.” Balzac had dealt with this subject in at least two other short stories: Gambara and Massimilla Doni, although reflecting on it through the creation of music rather than painting. Picasso, in turn, had made the “creator-creature” relationship one of the recurring motifs of his engravings at least since 1914 and throughout the 1920s, precisely dealing with it from the point of view of the painter and the relationship with his model.

Balzac-Picasso’s Le Chef-d’oeuvre Inconnu is not the only editorial effort in Vollard’s career. The gallery owner carried out several other similar projects, involving writers and poets such as François Villon, Mirbeau, Verlaine and artists such as Marc Chagall to name just a few, inaugurating an extraordinary period in the history of art publishing.

Finally, let us recall an anecdote. In 1961, when Picasso recounted the making of the Vollard edition, he downplayed and almost contemptuously said that the project was but a simple improvisation, suggested to the gallery owner by a friend. However, in 1936 the artist rented a studio on Rue des Grands-Augustinis, choosing it from many possible places he was considering. The studio happened to be right where Balzac’s story is set, perhaps a sign that Frenhofer’s memory must not have left Picasso completely indifferent. The artist kept the studio for almost twenty years, and it is precisely in that studio that he painted Guernica in just 10 days. The place of the unknown masterpiece became the place of his most known masterpiece.

Bibliography

Agamben, Giorgio. The Man Without Content. 1999. Stanford University Press.

Bachmann, Ingeborg. Letteratura come utopia- Lezioni di Francoforte, 1993, Adelphi, Milano.

November 25, 2020