From grades to tales: how Pop Art undermined the art writer

A brief, documented history of how Pop art changed art writing, including a few philosophical ideas for the art writer ot today.

There used to be a time when art writers would give grades. People called them critics. A top mark given by a certain authority would mean the artistic and economic success of an artist. A bad mark, a failure. When this stopped, tales took the place of grades in the toolbox of the art writer. Why and how this change happened are questions for the art historian and contemporary speculator. Here we try to take both roles, using an assemblage of found documents from the Pop Art period to think of the radical remaking of the profession. Finally, we will take a look at how the storytellers born from the ashes of the Modernist critics are still alive, and how much they owe to artists.

Shaving the Highbrow

In 1950s New York, the intellectual and authoritarian art critic was king. The prominence of entire artistic currents, notably Abstract Expressionism, was dependent on the liking of individuals equipped with great intellectual skills. Expertise reigned. Whether bashing or praising, the duty was judging. For the art writer of the time, suspension of belief was no option, so much so that critics of the critics even wrote entire books about the subject–see Tom Wolfe’s The Painted Word, written 15 years after the period in question, according to which art had become more an illustration of the critic’s theories than expression of the artist. In this context, the relation critic-artist-public was tense. Writes Lisa Phillips:

Several critics emerged as articulate and powerful spokesmen for the new American vanguard [and] for the first time, writers with literary credentials were publishing essays about advanced American art for an enlightened public. [Their] pronouncements became increasingly formulaic, exclusionary, and dogmatic.

To give some examples of the tone, the quintessential critic of the time Clement Greenberg once stated that “when you don’t like something, the words come more readily.” Even critic-turned-artist Donald Judd would write comments of this kind: “These paintings are momentarily pleasant and subsequently baffling and irritating.” (1960 review of Charles Alston’s works).

The period of the art critic as king came to an end. Art world intelligentsia in the form of writers could not live in the liberal United States, where – unlike today – authoritarian and paternalistic attitudes were incompatible with the freedom promised by the American dream and model. There was no room for perennial adult schooling, and the bottom-up approach was to prevail even in connection to liking art. Pop Art drove this change. Grading stopped. Telling began.

Angry Grandfathers

Before turning to how the critic transformed into a storyteller thanks to Pop Art, it should be mentioned that attitudes of art writers in Europe were not different from those we’ve been discussing so far. Authoritarian voices speaking in the culture section of newspapers had been active for even longer than their American colleagues, possibly providing a model to them. However, the European loud critical voice had taken strong political stances on top of artistic criticism. For example, realising how Paris had to give way to New York in the race for the art world hegemony, French critics were especially angry. At times, art writing could even be completely emptied of aesthetic or art theoretic statements, becoming political commentary if not outrageous rant. Images of American art landing in Europe thanks to their military machine (see military planes at the Aviano base) didn’t help ease the tones, and even prompted speculation that the arrival was a tool of propaganda.

Following the European coronation of American art as the new vanguard at the Venice Biennale in 1964, an unidentified French critic in the France Observateur bashed on it by appealing to its lack of revolutionary spirit otherwise found in the European pre-WWII avantguardes. The critic also claimed that the arrival of American art was a marketing campaign supported by the large capital of influential galleries and collectors from New York. Despite its angry tones, his art writing still went back and forth between aesthetic judgment and politics, which was no longer the case in the strictly political and racist attacks of French art critic Pierre Cabanne. As reported by Liam Considine:

The headline of Pierre Cabanne’s review of the 32nd Venice Biennial of 1964 conveys the visceral reaction from French critics: “In Venice, America Proclaims the End of the School of Paris and Launches Pop Art to Colonize Europe” […] Cabanne unleashed pent up French anxiety over the impacts of Americanization, regrettably descending into a shocking xenophobic and racist tirade that displaced decolonial anxiety onto Pop Art: “[The Americans] have treated us as poor backward Negroes, good only for colonisation. The first commando is in place: it’s called ‘Pop art.’

Not Caring

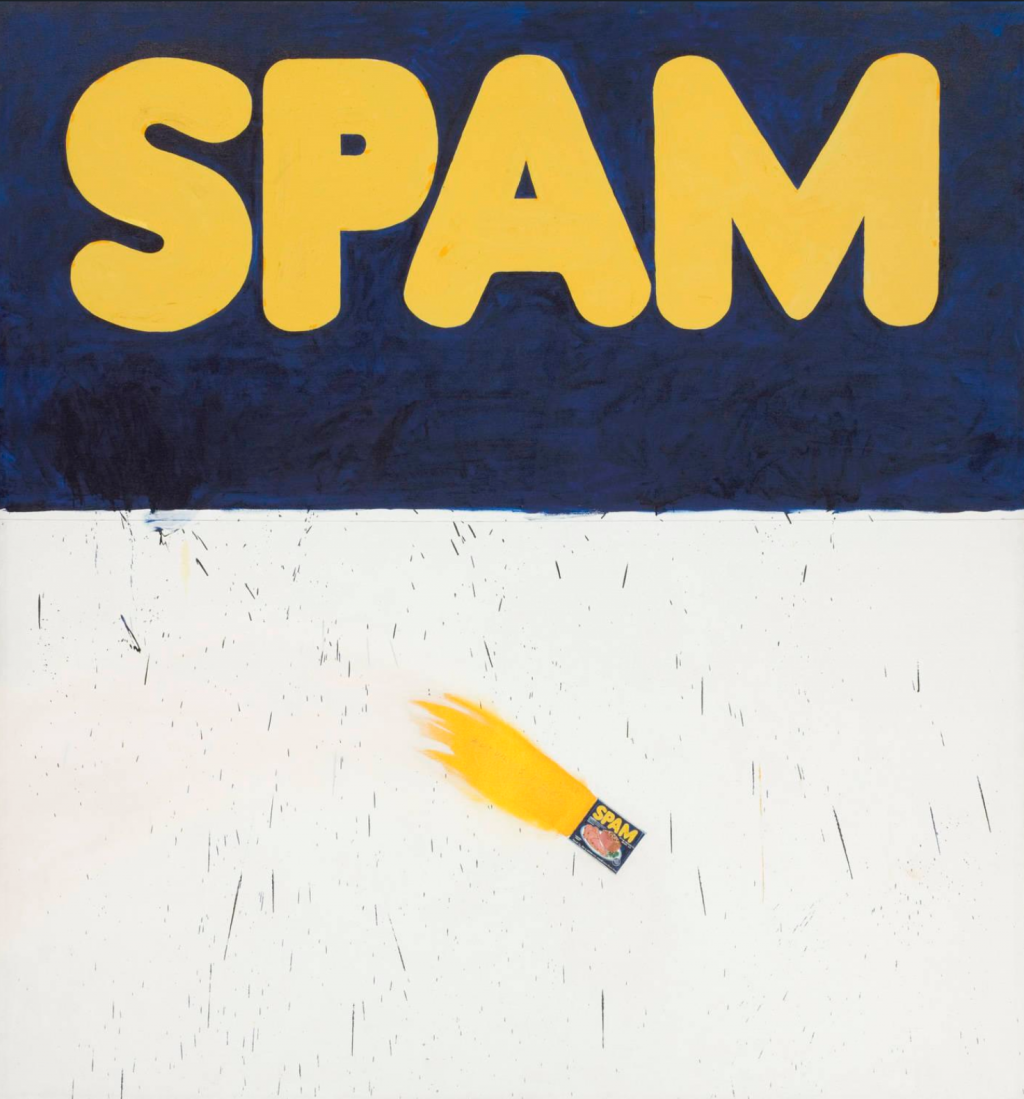

Among other things, what is remarkable about Pop Art is how it managed to upset art writers across the board. It not only unnerved French racist critics losing their geopolitical throne, it also angered American art writing establishment. Writes Lisa Phillips:

Pop artists were thrust into the spotlight and were quickly embraced by dealers, collectors, institutions, and the media. Glossy magazines covered this new phenomenon, nouveau riche collectors clamored for it, and people who didn’t know much about art responded to it because it depicted something familiar, something they knew. But one group that did not jump on the bandwagon was the art critics. Pop was an affront to all those who had supported the humanistic values of Abstract Expressionism. […] Critics saw Pop as decadent, immoral, anti-humanistic, and even nihilistic.

The commercial and public success of Pop Art despite the critics brought the grading to the end. The irrelevance of art writing as people knew it was upcoming. Artists understood that fame, recognition, and money could be obtained regardless of what a bitchy review might say about them and their work. Moreover, thanks to technological improvements, images of artworks were circulating more easily than before, making written descriptions of them in reviews rather useless. All of a sudden, art writers found themselves stripped of their power and role, which had to be reinvented.

Everyone is an Artist, Especially Artists

The success of Pop Art is arguably the merit of the media literacy of Pop artists. However, as exemplified by Andy Warhol, firm grasp of the codes of mass communication was not sufficient. Unfamiliar content sent via those channels remained necessary. The difficult balance between the conventional and the uncanny had to be found, and some of those seekers were especially good at the quest. One lesson for the art writer was clear: the time of academic expertise was over, at least outside academia. Rational arguments and scholarly grading had to be abandoned in favor of a more functioning approach in the liberal context, that is the one of artists themselves. Writing about art needed to become artistic writing. Writers had to abandon science to reach science fiction. Grades had to become tales.

As we have reported it so far, this shift in art writing is a speculation within art history. The documents we have presented come from the past. However, it seems to us that the fictional and narrative approaches to art writing that originated in the 1960s are still of use today, at least for the non-academic publications. Creating or expanding a tale about an artwork can still be the most relevant task for art writers, and for the skeptics out there, we think there are philosophical theories that justify this belief. On the one hand, one can think of Danto’s famous 1970s definition of art in terms of “aboutness,” as an object whose very nature is to allow for narratives that are not necessarily experienceable in the object itself; on the other hand, one can check the more recent position of speculative philosophies, according to which art should function as a metaphorical language to grasp a fleeting reality, and as we propose in an previous piece, so should art writing to grasp art itself.

Making a Point

We can ask whether the disappearance of the art writer as a grader bettered the art world. Are texts with explicit value judgments, firm academic language, blunt political opinions, and straight descriptions better for the subject than their fictional and narrative counterparts? This is a difficult question for the critic of the critic, for the art writer of the art writer. Another article will deal with this separately. We can nonetheless try to make a final point, which is about the importance of text on art in general. Contemporary art is not music, it is not a Hollywood film, it is not sublime landscape painting. The formal qualities of the contemporary artwork are not sufficient for its existence. Ever since the historical avant-gardes, art has been dependent on the institutions that legitimate it, first of all language.

It seems obvious that the extinction of the Modernist critics in the 1960s gave rise to the currently dominant species of the curators. Especially in the beginning of their era, curators were the new custodians of art writing, and later of the disappeared value judgement in art. There is a catch though. Where critics would express their negative opinion in writing, sometimes creating stars from their nastiness in words, contemporary curators express dislike by means of silence. Unappreciated work disappears via avoidance of it. Non-language is now the tool for slating.

Bibliography

Considine, Liam. American Pop Art in France: Politics of the Transatlantic Image. 2019. Routledge

Judd, Donald. Complete Writings 1959-1975. Judd Foundation

Phillips, Lisa. The American Century. 1999. Whitney Museum of American Art

Wolfe, Tom. The Painted Word. 1975. Farrar, Straus & Giroux

May 14, 2020