Five self-portraits at the time of surveillance capitalism

What takes you from facial recognition algorithms to a museum of ancient art? The hope of finding an antidote to big data.

What mysteries lie behind a self-portrait? Every age has its own secrets. In our digital era self-portraits have turned into a mass phenomenon called Selfie, whose real function is however becoming more and more shadowy. Last year author and tech consultant Kate O’Neill wrote a tweet that was reposted by more than 10.000 people in just a few hours [link. Ed.]. She was suggesting that all the images of those who take part in the 10-Year-Challenge on the various social media (that is posting side-by-side portraits of yourself 10 years ago and now) could actually be used to train facial recognition algorithms on age progression.

As Kate O’Neill, who has investigated the relationship between technology, images and freedom in her book Tech Humanist: How You Can Make Technology Better for Business and Better for Humans (2018), also American researcher Shoshana Zuboff addressed this subject in her book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. Talking about the third-party data collected from the web, Zuboff went so far as to describe how the development of Artificial Intelligence applied to people’s facial images (the self-portraits that we all voluntarily give to Big Data) is convenient for any government that want to have total control over its country’s population, and how this already happens in many countries.

The theories of Kate O’Neill and Shoshana Zuboff, as disturbing as they might be, are only the latest chapter in a long history that interweaves images with self-perception and power. But the topic of self-portrait hides subtle mysteries that go even beyond technology. Take one of the many self-portraits in art history, perhaps one in which the artist represents himself in the act of painting. What does he want to imply? Does he look at us with the aim of depicting us or does he want to ‘judge’ us instead? And if the artist looks himself in a mirror, does he do it to portray himself or, rather, to judge himself?

These are but a few of the questions that art historian James Hall asked himself in front of the “paintings that look back at us”. To answer those questions, Hall carried out extensive studies which merged into The Sefl-Portrait. A Cultural History (2014), a wonderful survey that ranges from antiquity to the present, and which is undoubtedly a fundamental reading for anyone who wants to approach the subject.

Moreover, self-portraits also raise questions that are not just philosophical or psychological. These works, effectively, can bring to light various processes of artistic culture that along the centuries have enriched themselves with new nuances. We have focused our attention on these latter aspects of self-portrait. And we have decided to embark on a journey in an attempt to show the development of this very fortunate practice. We shall avail ourselves of works that are housed in the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan: our itinerary begins in the 16th century and takes us to the threshold of Futurism.

[In regards to James Hall’s book and self-portraits see also this feature we published. Ed.]

Let’s start off with the work above. It is displayed in room XIX , and during a visit to the museum it might even escape visitors’ attention. Room XIX is dedicated to portraits, and among those on the walls are some really superb ones. There is the Portrait of Count Antonio di Porcia and Brugnera by Titian. There are the Portrait of Febo da Brescia and the Portrait of an Elderly Gentleman with Gloves by Lorenzo Lotto. There is a Portrait by Tintoretto, there is one by Giovan Battista Moroni, and several others ‘selfies’. The characters in these paintings look straight out at us. Their gaze is very powerful indeed. And our little girl with big eyes could almost disappear by comparison, also because of the small size of the canvas, which measures 36 x 29 cm only. Yet this small painting is a fundamental record of sixteenth-century portraiture.

The work is dated 1560-1561 and is presented as a Self-portrait of Sofonisba Anguissola (Cremona, 1532 – Palermo 1625), one of the very few women artists of the Renaissance who managed to have a successful career, not only in Italy. The small canvas is one of her late works, perhaps painted for the court of Madrid. It expresses Anguissola’s mature style and the careful attention she pays to calligraphic details, such as her hairstyle, the embroidery on her shirt, the fur collar, the fluid shadows on the pearls and rubies in her hair, and in general the reflections of light that meet every reflective surface, even her pupils.

According to some art historians, this is not a self-portrait, but rather the portrait of one of Sofonisba’s sister, Minerva (see the portrait of Minerva preserved in the Museo Poldi Pezzoli, also in Milan). Either way, this doesn’t really matter. The painting has no symbols, it doesn’t really say much about the subject, at most we can gather she belonged to a upper class. What this painting shows instead is Sofonisba’s painting skills. The main character of this work is not the painted character as such, but rather the virtuosity of the artist who painted it. The portraits of Sofonisba’s sisters were indeed painted as show-pieces to attract potential buyers.

The faces painted by Sofonisba “are executed so well that they appear to be breathing and absolutely alive”, wrote Vasari in his Vite, after visiting the artist’s childhood house in Cremona where he saw her works in person, two years before publishing the second edition of his pivotal book. It was 1566, Sofonisba was 34 years old and was already one of the most famous portraitists of her time. She had five sisters who had all been encouraged by their father Amilcare to learn painting. They all painted and portrayed each other. Sofonisba – the best one – studied with Bernardino Campi, one of the leading painters of the time.

[Here is a link to our writing about San Paolo Converso in Milan, a former church preserving an extraordinary decorative cycle by the Campi brothers. The charming church is now an active contemporary art space. Ed.]

In 1559 Sofonisba was invited to the court of Philip II of Spain to portray his wife and become her art teacher. Sofonisba’s father and agent had created a thriving market for his daughter’ self-portraits, who had by then become a “reliable brand”. As poet Annibale Caro wrote to Amilcare Anguissola:

I desire no better than the portrait of Sofonisba, so that I may show two wonders at once, the work and the artist.

But the self-portraits of the painter are not only a sought-after commodity by the sixteenth-century market: to the artist is owed what is considered to be the first self-portrait, signed and dated, in the history of Italian art. It is a work from 1554 and is now preserved in Vienna. In the painting, the girl looks younger than she was at the time, and holds a book in her hands. The painting is not very different from others by Sofonisba (today there are 12 of them left in different museums and collections). Different objects with their related symbols of culture, spirituality and elegance enter the painter’s composition scheme. After a series of these self-portraits, more or less similar in tone, there comes a twist.

It is 1559. The painting is titled Bernardino Campi painting Sofonisba Anguissola (Giovanni Morelli was the first one to identify the two artists in the painting and to suggest the attribution to Sofonisba, which was later confirmed by Berenson and now shared by everyone).

[Here the link to our writing on the ‘dark’ connoisseur Giovanni Morelli. Ed.]

The painting is now preserved in Siena. At first glance it may look like a portrait of Bernardino Campi while he is at work. As a matter of fact it is not a portrait: it is a self-portrait. Sofonisba is depicted on the canvas that the painter is about to complete, but her size and preciousness of the figure overwhelm that of Bernardino, to the point that he seems to take a back seat.The young, virginal, modest Sofonisba is no longer the girl who appears among the details of everyday life as she did in her previous self-portraits. Sofonisba is no longer even a simple painter: Sofonisba is the painting herself. The humble and talented little girl wants to depict herself as Allegory of Painting. The small canvas in the Pinacoteca di Brera and this work clearly talk to each other. In the former painting is the protagonist. In the latter the protagonist is the Painting.

Self-portraits in which the artist identifies himself as allegory of his own art will become a central motif also in the following years and later centuries. It happens for instance between 1580 and 1584 with one of the first self-portraits by Palma Giovane (Jacopo Negretti). The painting is also housed in the Pinacoteca di Brera, albeit it is not on show. Palma Giovane (Venice 1584-1628) trained with Taddeo and Federico Zuccari, and was then influenced by both Titian and Tintoretto. His artistic breakthrough however can be pinpointed in 1579, when he was called to decorate the Sala del Maggior Consiglio in the Doge’s Palace in Venice. According to art historians, Palma’s self-portrait that is preserved in the Pinacoteca immediately comes after that, and it is an evident expression of him being aware of the leading role he was playing on the city’s art scene. It can be clearly spotted in the painter’s almost arrogant pose. Palma was to become a prominent artist in Venice for several decades and was courted by the post-conciliar church to paint new altarpieces for the churches of Venice and by the State for its official paintings.

Francesco Hayez took inspiration from Palma Giovane for his Self-Portait at the Age of Fifty-Seven, that is preserved in the Pinacoteca di Brera and has recently been restored. Hayez, who considered himself heir to the great Venetian school, so signs the painting: (in italics with marker pen) “Fran. Hayez/Italian of the city of Venice/ painted 1848”. While the composition of the two paintings can’t really be compared, the artist’s look reveals the same self-confidence that Palma also showed, as if to say “painting is me”. In this case however Hayez turns the self-assuredness of his predecessor into a sober, actually severe sternness, thus creating a solemn atmosphere rather different from his two previous self-portraits: Self-Portrait in a Group of Friend, ca. 1824 and Self-Portrait with Tiger and Lion, 1830, both housed in the Museo Poldi Pezzoli. Hayez regarded his Self-Portrait at the Age of Fifty-Seven as one of his best works and kept it in his studio until his death, more or less as Vermeer did with his The Art of Painting also known as (Painter in his Studio), that is considered to be the only self-portrait of the artist, (albeit from behind). The painting remained in the artist’s studio until his death, it was never sold, and is housed – by coincidence- in the same museum – the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna – where the Self-Portrait with open book by Sofonisba is also kept.

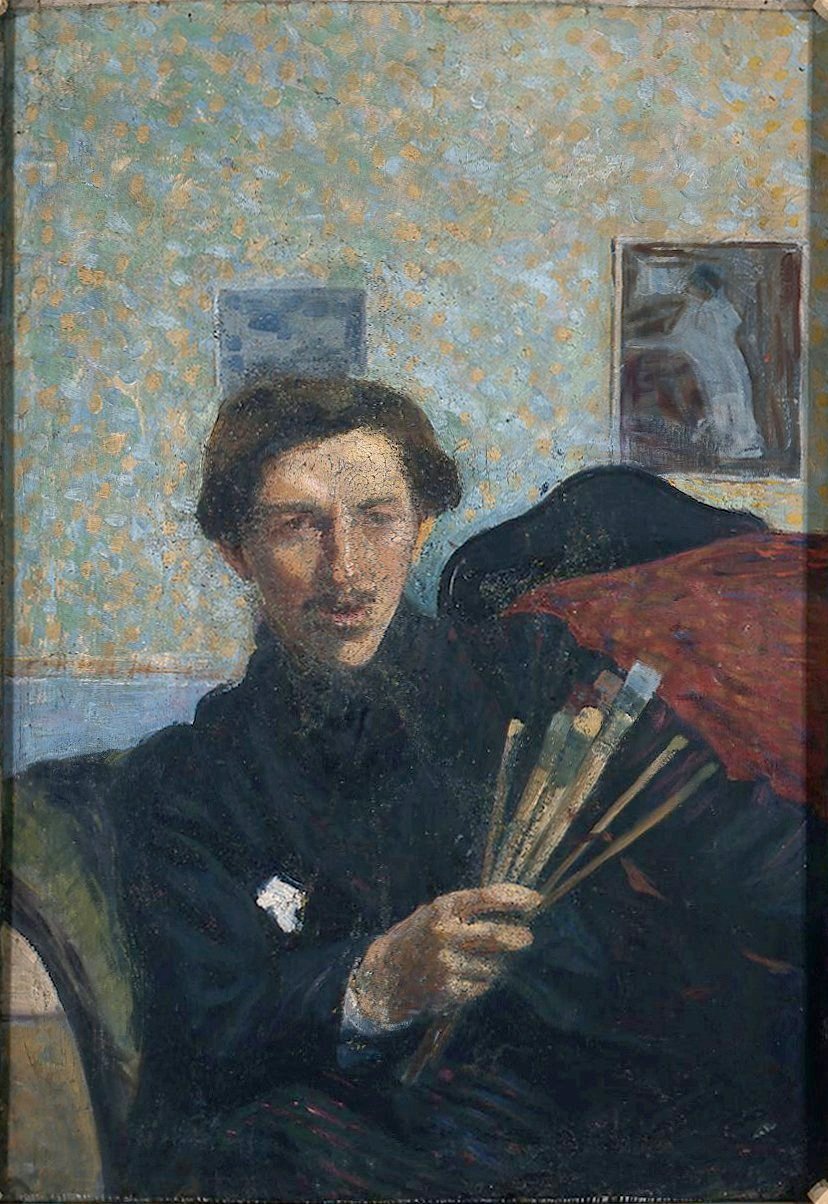

The fierce gaze, the works on the wall, the brushes in his hands, these are all elements that also recurs in a Self-Portrait by Umberto Boccioni. Surely datable before 1908, this painting, compositionally, is along the lines of Sofonisba, Palma and Hayez’s works. However, the painter, who was soon going to be a Futurist, must have been fed up with the intimate atmosphere of those works. Thus, Boccioni covered the painting with thick grey brushstrokes, as though he wanted to entirely erase it. This work was discovered some time ago on the back of another canvas on show in the Pinacoteca di Brera – that is another self-portrait by Umberto Boccioni, yet completely different.

This time the artist portrays himself outside the flat where he lived, in Via Adige 23, in Milan, and not in his studio. He is probably referring to this painting in his Taccuini Futuristi, when on May 13th 1908 he writes down:

I’ve just finished a self-portrait that leaves me completely indifferent. I am tired and I don’t have any new idea. No one writes me, I have a nice time with her [the mother. Ed.]. In quite good spirits.

In 1908 the artist is eager to experiment new forms of composition. In this self-portrait you can spot very clearly the outskirts of Milan in the background. The representation of the city is going to become a significant motif in the artist’s practice as it appears in his painting The Morning (1909) where the actual protagonist are the outskirts themselves. The year after he paints The City Rises, whose subject in this case was inspired by what he saw from the same studio-flat of the Self-Portrait that is housed in Brera.

One of the preparatory sketches for that fundamental artwork, an oil and tempera on paper, can be found just a few rooms away in the same Pinacoteca di Brera. Also Hayez, in his Self-Portrait with Tiger and Lion, moved the subjects of the painting outdoors. Setting the scene outside the studio wasn’t something new. Let’s have a look for instance at the work by Maarten van Heemskerck, painted in 1553, which is a conceptual double self-portrait, where the artist is depicted twice: he portrays himself in the studio as well as in the act of painting outdoors. What is new in Boccioni, is that he has included both a portrait of himself and of the object of his research in a single painting. A poetic statement that was soon going to explode, literally, into Futurism.

Bibliography

AA.VV., Il Ritratto italiano, Bergamo, 1927

S. Mason Rinaldi, Palma il Giovane. L’opera completa, Milano 1984

F. Mazzocca, Francesco Hayez. Catalogo ragionato, Milano 1994

Umberto Boccioni, Taccuini Futuristi

J. Hall, The Sefl-Portrait. A Cultural History, London, 2014

November 25, 2020