Lucas Blalock: a criminal, a lover, an old man, a policeman, an artist, a spy, a nice guy

An in depth look at Lucas Blalock’s performative approach to photography, and the dynamic relationship to art history at play throughout his work.

If photography were a tennis partner, as Lucas Blalock likes to consider it, what kind of partner would it be? Serena Williams, a retiree wearing an all white Lacoste tracksuit, or just a dumb automatic tennis ball machine? Throughout the years Lucas Blalock has played with many of the tennis partners photography could embody. He has played indoor and outdoor, with a distinctive affinity for the synthetic turf court of Photoshop. However, the performative nature of his approach hasn’t been addressed as much as some of the more conspicuous aspects of his work. Blalock could indeed be compared to a lonely stage director filling in as many roles as possible by himself, or to an unrelenting standup comedian, performing a low budget one-man show with cheap props on one of New York’s few affordable stages — a tabletop in his living-room.

Occasionally, he gets on stage and puts on an act as a boxer ready to throw a jab at the puritanical little box that is photography. In his 2009 picture, The Contender, we see him shirtless and disheveled facing an unseen opponent. He holds his fists up and looks at the unknown challenger with an expression of fear, bravery, and disbelief heightened by the Caravaggesque lighting of the scene. Who is Lucas Blalock taking on? Is it photography and its ungraspable terms in today’s digital mess, a group of jacked-up conservative bros, or just himself and his own demons? There is a willfully pathetic imitation of masculinity at work in this picture of the artist as a skinny contender. Unassumingly, Lucas Blalock happens to resemble Pierre Bonnard in his 1931 self-portrait Le Boxeur (portrait de l’artiste) (here is our paper about the seminal Pierre Bonnard exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay). Contender Blalock and Bonnard Le Boxeur respectively depict themselves as somewhat inadequate, trying to cope with a reality bigger and more violent than they were ready for. Formal parallels such as the idiosyncratic pictorial treatment of the fists add to the similar attitude of the two depictions. Bonnard’s pink and red fists contrast with an otherwise yellowish monochromatic canvas. Correspondingly, Lucas Blalock who is known for his “ham-fisted” use of Photoshop turned his own fists into ham-colored masses and the skin of his right bicep into a deceiving patch of digital flesh.

This theme of the boxer is again found in a picture by Jeff Wall. Boxing (2011) shows two teenage boys who look like they could be brothers sparing in their parent’s upscale living-room. A piece by Josef Albers hangs on the wall between a white brick fireplace and built-in shelves on which vases and decorative objects are tastefully arranged. In front of the fireplace a pot of white orchids sits on a low marble table between two stiff leather couches. Wearing boxing gloves and shorts, the two shirtless fighters sparing near the couches become part of the immaculate interior in spite of their disruptive activity. In a mannered way, the picture is anxiously balanced between this pristine decor and the staged depiction of an already coded type of violence. Wall, who himself mentioned that the photograph originates from a childhood memory of boxing with his brother, deployed considerable means to create a picture that grants him the analytical pleasure of a mediated and disembodied look at the physical activity.

While Jeff Wall’s picture relies on the stability of a classical idea of the tableau with its harmonious composition, Blalock’s picture functions as an expressive vessel filled with dramatic intensity. Wall’s photographic tableaux played a critical role in Lucas Blalock’s ability to conceive the terms of his own activity of picture-making, yet there is a cardinal difference in the way Blalock tends to devise and activate what could be described as the picture’s embodied potential. This embodiment not only plays out within the photograph’s pictorial space as when Blalock expresses his wish for a picture to “act up” and do more than merely describe or catalog the world, but is also at play in the picture’s physical existence as an object in the world. In recent exhibitions, Blalock also pursued this conception of the picture’s embodied potential by having photographs set on metal rods. The anthropomorphic quality taken on by the now double-sided objects is counterpoised by the inevitable allusion to advertising while reminding us of Lina Bo Bardi’s glass easels. His attitude towards the picture as an entity that can either sit on the wall or be handled in more unceremonious ways is closer to the considerations of contemporary painters such as Laura Owens (here is our interview with Laura Owens), Jana Euler and Jutta Koether, or the early work of Jörg Immendorff. Though talking about sentient objects would be venturing on a slippery slope, the picture does become a kind of performer in its own right, or is at least imbued with a performative potential.

Lucas Blalock’s aforementioned one-man show began when as a young artist he had to come to terms with the difficulty of engaging with the scale and level of production of an artist like Jeff Wall. “I was really attracted to Godard because he’d made films on a really small scale. At the time, photography felt much more in the scale of somebody like Andreas Gursky or Jeff Wall and these big fantastical productions…” In turn, Blalock developed his own set of tools informed by Bertolt Brecht’s ideas on theatre. Not only did he start bringing the “offstage” labor of Photoshop into the picture, he also took up other Brechtian traits such as multi-roling, minimal sets, simple lighting, and the use of symbolic props that can become multiple things. A good example of the latter is the Philip Guston inspired Shoe (2013) diptych displayed at MoMA’s New Photography exhibition in 2015. Altered through simple cartoonish black lines, a sports bag resting on a tabletop purportedly stands in for a shoe, which is itself treated as a surrogate for a piece of meat placed on a sheet of newspaper. This still-life slapstick bears the humor of early cinema as in Charlie Chaplin’s iconic cabin scene in The Gold Rush (1925) where Chaplin diligently cooks his shoe to share a shoe-lace spaghetti dinner with Big Jim.

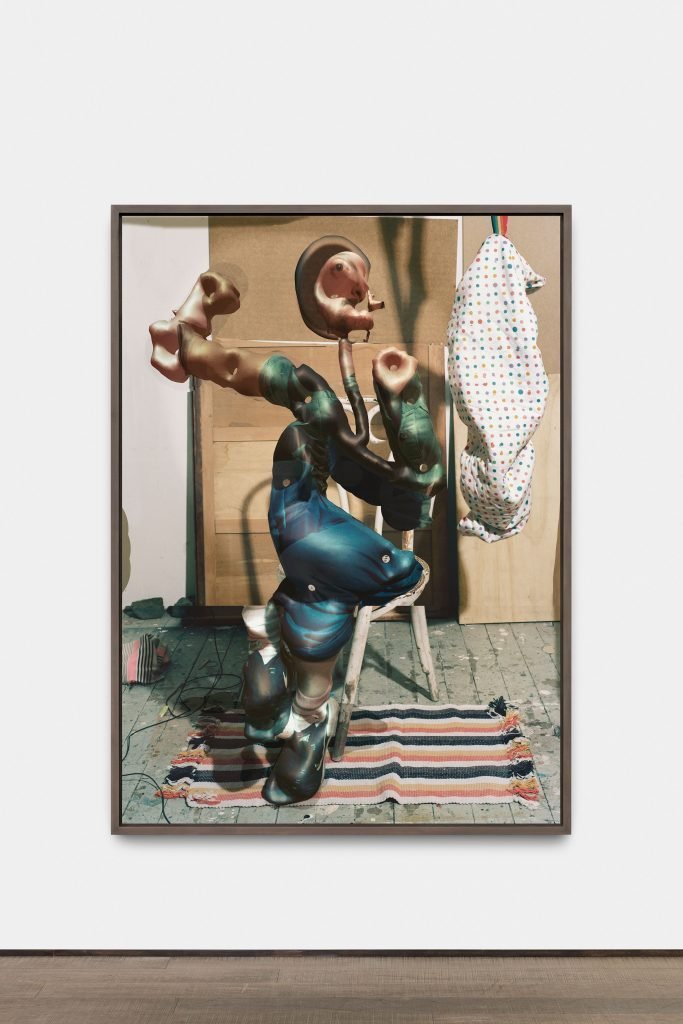

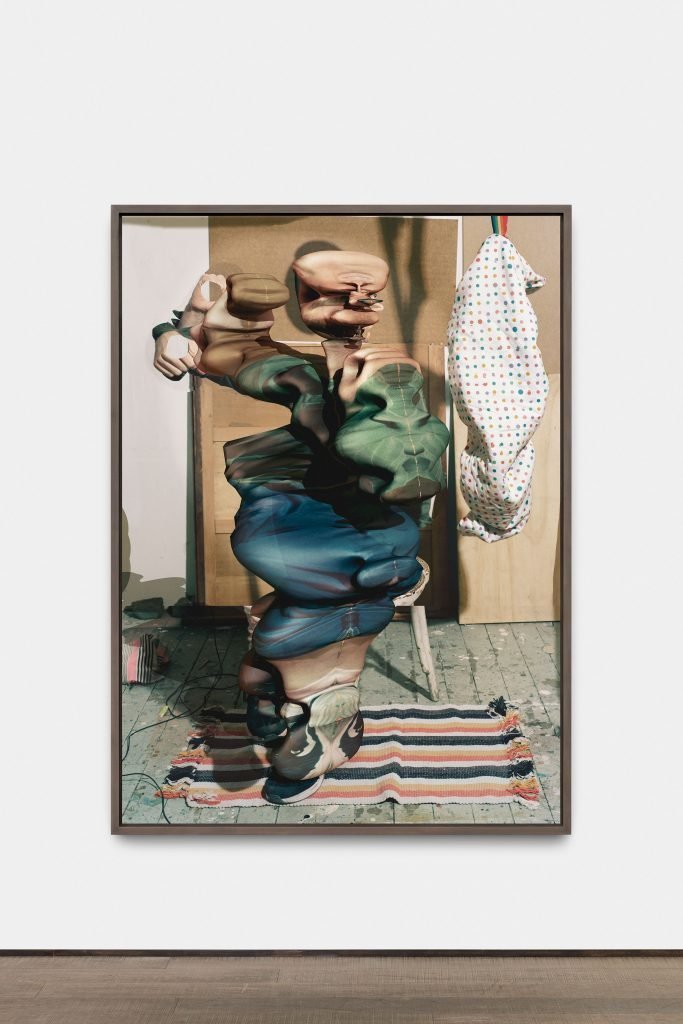

Following his two largest solo exhibitions to date at The Institute of Contemporary Art Los Angeles, and the Museum Kurhaus Kleve, Insoluble Pancakes at rodolphe janssen is one of Lucas Blalock’s most concise shows yet. With just five large unique prints, the exhibition consists of self-portraits made from digital combinations of five 4×5 negatives taken moments from one another. These pictures of the artist floundering about on a bistro chair in front of pieces of cardboard and plywood leaning against the wall of his studio are at once stripped down and epically baroque. Blalock pushes photographic software to its limits by using the available 3d features to reshape, contort, inflate and deflate his body like an out of control shape shifter. As in The Contender, Lucas Blalock’s gestures have the pretense of a boxer with multiple fists hovering around his body. This time however, we are not inclined to imagine any unseen opponents, we just see the artist more or less peacefully dealing with himself.

Lucas Blalock, #3 policeman (Wholly Holy), 2019, archival inkjet print, 188 x 135.9 cm. Courtesy the artist and rodolphe janssen, Brussels. Photo: HV photography

Lucas Blalock, #4 Divney (Popeye), 2019, archival inkjet print, 188 x 135.9 cm. Courtesy the artist and rodolphe janssen, Brussels. Photo: HV photography

Lucas Blalock, #11 Fox (Trapper), 2019, archival inkjet print, 188 x 135.9 cm. Courtesy the artist and rodolphe janssen, Brussels. Photo: HV photography

Lucas Blalock, #1 de Selby (Gregor), 2019, archival inkjet print, 171 x 135 cm. Courtesy the artist and rodolphe janssen, Brussels. Photo: HV photography

Lucas Blalock, #2 The Orphan (Darko), 2019, archival inkjet print, 188 x 135.9 cm. Courtesy the artist and rodolphe janssen, Brussels. Photo: HV photography

Blalock plays multiple roles inspired by protagonists from Flan O’Brien’s novel The Third Policeman (1940) and popular culture characters like Popeye. Each picture has one name followed by a second option in between brackets. This activity of naming, which gets performed through the camera’s relationship to bodies and objects in Blalock’s work, is furthered through the tilting of the pictures themselves. There is an interesting parallel to be drawn between this literary activity in Blalock’s exhibition and 1970s conceptual artworks like Douglas Huebler’s famous Variable Piece #101 (1973). In this work Huebler sequentially photographed Berndt Becher while asking him to “look like” a priest, a criminal, a lover, an old man, a policeman, an artist, Berndt Becher, a philosopher, a spy, and a nice guy, before sending him the photos two months later in a different order, asking him to link them back to the given terms. In a “post-conceptual” fashion, Blalock takes up such strategies and lures them back into the pleasurable realm of the pictorial through a literary door.

If photography used to be Lucas Blalock’s tennis partner, the pictures presented in Insoluble Pancakes show an even more embodied approach. Here, photography is a frog trying to blow itself up to become an Ox. Blalock allows it to be an exteriorized energy that moves between physical, pictorial and digital spaces, seemingly conjuring the ectoplasm of late 19th century spiritualist photographs. Functioning like motion studies of their own making, these self-portraits show photography as a skin that one wears and grapples with in an attempt to grasp its hybrid, malleable, porous and unforeseeable terms.

***

Emile Rubino is an artist by night and an art worker by day. He lives in Brussels where he makes pictures, writes, and occasionally curates exhibitions. Rubino is also the self-proclaimed editor in chief of the first issue of Le Chauffage, a collaborative magazine yet to be published.

Lucas Blalock is an artist based in New York. For our Proustian questionnaire with him, click here.

November 25, 2020