Monoculture and the directorship of M HKA: an interview with Nav Haq

We talk to Nav Haq, associate director of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Antwerp M HKA, discussing monocultures and his recent promotion.

The Museum of Contemporary Art in Antwerp M HKA is one of the largest of the region comprising Belgium, The Netherlands and Luxembourg. It is a venue for large scale, temporary exhibitions, as well as the holder of an important collection of contemporary art. We spoke to its associate director Nav Haq on the occasion of his recent promotion and the opening of the last exhibition he organised at the museum titled Monoculture – A Recent History.

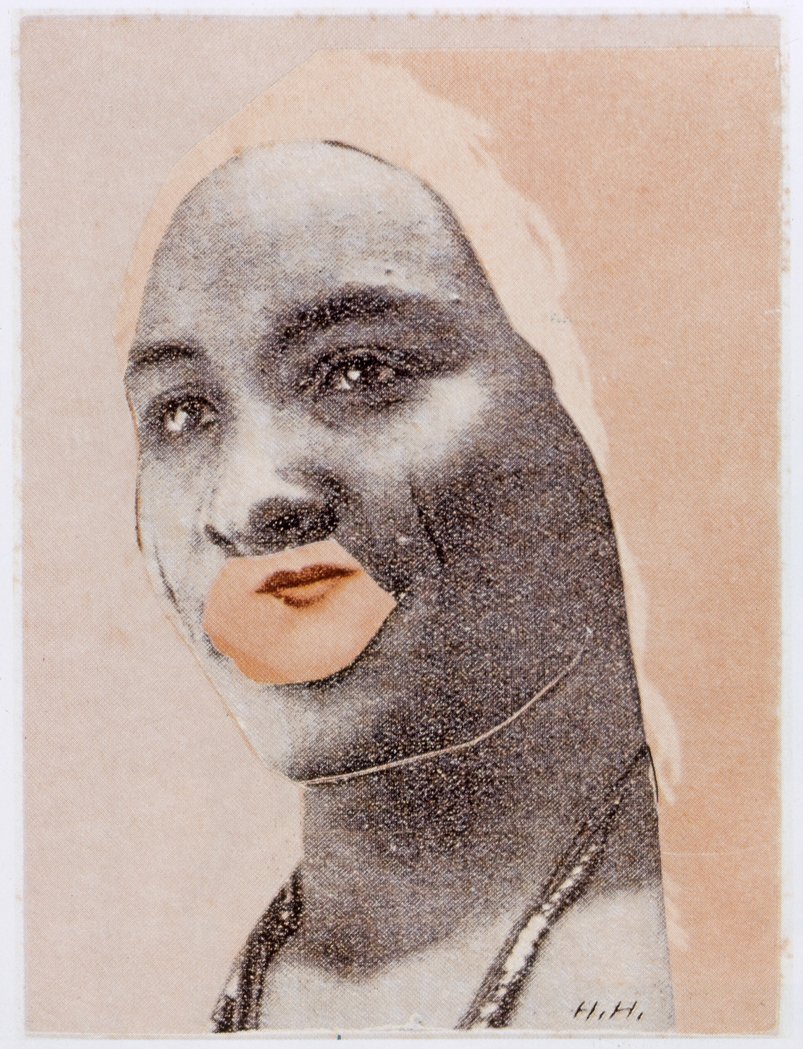

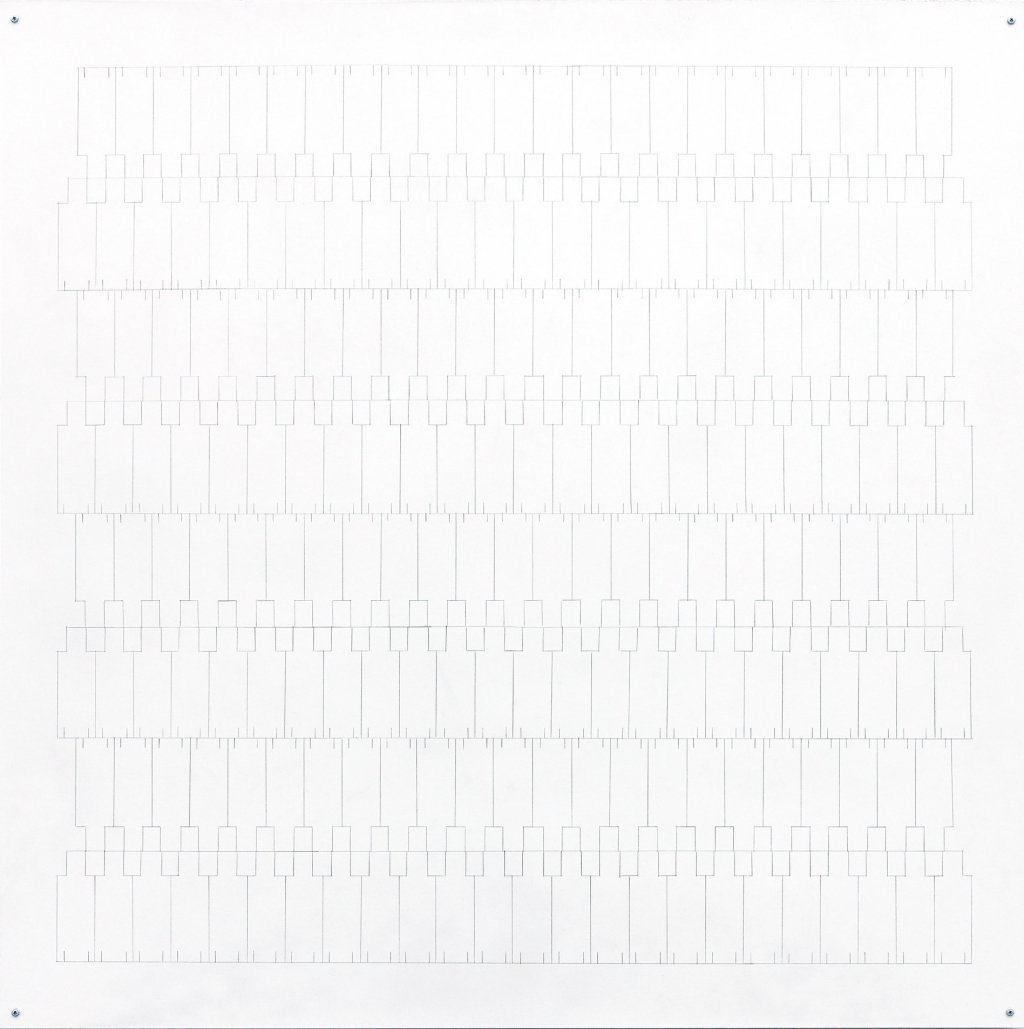

Nav Haq’s successful career has brought him to collaborate with artists such as Hassan Khan, Cosima von Bonin, Shilpa Gupta, Imogen Stidworthy, Otobong Nkanga and Cevdet Erek. He has also organised significant overviews of work by Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin, Joseph Beuys, Kerry James Marshall and Laure Prouvost, as well as curating the Goteborg International Biennial of Contemporary Art in 2017. During his previous experience in his home country (the UK), he held curatorial positions at Arnolfini in Bristol and Gaswork in London.

You worked as a curator for M HKA for many years but you’ve been recently appointed associate director. Can you say a bit more about this change? What are the differences between the two jobs?

Nav Haq: What I did as a curator was focusing on specific temporary exhibitions. Although I am glad I can continue to do that, I now also have the overall responsibility for the artistic programme of the museum, leading the development of the artistic vision of the museum. This was previously a responsibility of our General Director Bart De Baere. He is now working heavily towards the eventual new building for M HKA, scheduled to be inaugurated in 2027. Now I have several additional responsibilities, including managing a team of curators and producers on the further development and implementation of the artistic programme including all those involved with production and technical aspects, plus I’m managing the coordinators and programmers of our cinema De Cinema. But developing an overall vision for the museum’s programme is an exciting new challenge.

Three of the biggest public museums in Italy (Uffizi in Florence, Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan and Museo di Capodimonte in Naples) are now run by foreign directors, a political move made in 2015 to assure an international reach and to avoid the risky self-referentiality of these institutions. You are the first non-Belgian director at M HKA. Do you think your appointment stems from similar political motivations in Belgium?

Nav Haq: For the record, I am a Belgian. I acquired Belgian nationality in 2019 on top of my British one. This was not to do with my job at M HKA, but partially to do with the political situation in the UK in leaving the EU. It also felt like a good idea as I feel integrated and happy here. My appointment wasn’t motivated by a broader policy like the Italian context you describe. M HKA launched an open call. I had to go through the formal process of application typical of public institutions and presumably I was chosen because they considered me the best candidate. Within the regional context, Antwerp has uniquely had many curators from elsewhere coming and going, certainly at M HKA but also at other organisations such as Extra City and Objectif Exhibitions when it existed. It is perhaps an echo or legacy of the period of the post-war avant-garde when many artists would pass through Antwerp and see it as a meeting point.

You organised the current exhibition at M HKA called Monoculture – A Recent History. It includes archival material, and existing and new artworks by international artists. Can you tell us a bit more about the show and what a visitor can expect to see and learn?

Nav Haq: First of all, it is interesting for me to see how people understand the word “monoculture” differently. In the Anglo-Saxon world, it is quite common to hear it in mainstream media or in social sciences in relation to society. Here people think of monoculture more in relation to agriculture, which is the context where the word originated. The overall topic is cultural homogeneity and the important question of what kind of society we want. There’s been a large focus on multiculturalism in societies in the recent years, which has often landed in clichés and stagnant debates. I felt it would be meaningful to think about what people consider to be the opposite of multiculturalism, certainly from a historical perspective. The exhibition proposes many different case studies of cultural homogeneity from the last 100 years, which I mapped during more than two years of research. This goes from some of the most monolithic examples of monoculturalism such as Nazism in Germany, communism in the Soviet Union and liberal capitalism in the American model, to less hegemonic ideologies including even some coming out of emancipation movements, for example the Négritude movement in Senegal intended as part of a post-colonial imperative, moving on to even religious and linguistic homogeneity, and of course agriculture. In the exhibition, visitors can encounter these case studies as a dialogue between historical and contemporary artworks, propaganda and documents of philosophical thought.

In a previous interview you mentioned that despite its self-given image of a multicultural city, Antwerp is rather monocultural. To what extent does the exhibition Monoculture deal with the city that hosts it?

Nav Haq: It doesn’t do it in a direct way. What I learned is that the things happening in the world or in your own context become a backdrop to a project in a way you can’t control. For example, the work by Ibrahim Mahama in the exhibition, a piece he made in response to a colonial-era statue in Antwerp of the Catholic missionary Constant de Deken who undertook missionary work in the Belgian Congo. The statue depicts a Congolese man kneeling at de Deken’s feet. It becomes pertinent once again in view of the recent Black Lives Matter movement. I try to work with those events in the most meaningful way I can. There are forms of nationalisms in this region and in Flanders. My way of reflecting on these is not necessarily by pointing the finger directly where they are, but more through their reflection in a broader context. The exhibition however features a few exhibits that have to do with the Belgian context, for example some artefacts on Belgian collaboration with the Nazis, or on the role of religion in public education during the so-called “School Wars” in Belgium.

[Here is our feature on Ibrahim Mahama in Tamale. Ed.]

At least before the pandemic, there has been a discussion around cuts of public spending for culture in Belgium. Has M HKA been impacted by these cuts and to what extent has it had to appeal to private sponsorship to keep up?

Nav Haq: M HKA did take a small cut, but the pandemic has clearly had a bigger impact on the museum’s finances, which largely rely on ticket sales. There is nonetheless no plan to radically reorient towards private funds, although we will certainly look to do so. Despite the growing demand to look for more private funding, I don’t think Belgium is yet that close to a neo-liberal model, at least not like the one I experienced when I worked in Britain. At the same time, there is no doubt that artists have been the hardest hit by budget cuts in Belgium. The pandemic has been a way to shine a spotlight on a specific issue: the precarious situation of those locally-situated artists and other cultural workers that might also form part of the ecology around the institution. We’ve been looking for different ways to support them, such as finding different kinds of employment for them, or initiating new projects, etc.

Because of the pandemic, many museums have turned their attention to online programmes. Has M HKA used the online medium at all? If so, can you tell a bit about M HKA’s presence online?

Nav Haq: It is probably not as invested as other institutions at this moment. During the first lockdown, where as you say everybody started to do things online, I actually had mixed feelings about this. The attempt to represent an exhibition online seemed very inadequate to me. I thought some public events were done very well, some not so. The thing I valued the most was screenings of artist films, made available by both public institutions and commercial galleries. One thing we are organising is inviting experts on certain topics such as colonial history or Nazism in Belgium to visit the Monoculture show, and publishing the recordings of their talks in podcasts. But as we are actually looking to do more as a museum in terms of public events, we will also look to hold some in a hybrid way – live and online.

M HKA is known to hold an extensive collection of contemporary art. Can you say something about the acquisition policy of the museum?

Nav Haq: It has evolved a lot over time. It was quite intuitive at the beginning it seems, having to do with acquiring pieces from the temporary exhibitions organised at the museum. Although this is still important for us, there is more structure to the policy now. It has three focuses. The first is image-making, based on the history of Antwerp as one of the founding places of modern painted images, which is still very relevant for many local contemporary artists and definitely the most popular thing with the public here. The second focus has to do with societal concerns, and the third with action or performativity. These are the three broad lenses we have for our acquisitions, but we also have specific geographical interests. On the one hand, we look at the so-called Eurocore region – that is the combined region of Benelux and the Rhineland in Germany – which is historically well-connected and is also the densest part of Europe. On the other hand, we increasingly focus on Eurasia, intended as the combined mass of Europe and Asia. This is understanding Eurasia as a plurality of culture. In the way we understand this term, a Fleming, a Turkic person, a Persian, a desi, a Tatar or a Han Chinese are all Eurasian.

Antwerp has a reputation as a city with many and important art collectors. As a museum director are you involved at all with this collecting scene in town and what is your impression of it?

Nav Haq: Some time ago I read an interesting survey according to which Belgium has more art collectors per square mile than anywhere else in the world. Curiously I don’t meet them that often. From my experience, they live less in the built-up areas but maybe more in rural places. They don’t seem to be collectors like there are in other places, motivated by investment or status symbols. They are instead people doing their own things, successful business people that just happen to be interested in art. They seem to collect in a way that is not about putting forward a particular self-image at all. As I say, they are interested, which I find rather refreshing.

February 16, 2021